José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949), one of Mexico's most influential muralists, painted this canvas at the beginning of his second and longest stay in the United States, which extended from 1927 to 1934, the year he completed his monumental mural at Dartmouth College, The Epic of American Civilization. Before arriving in the states, Orozco's work as a muralist supported the populist aims and leftist social commentaries of the mural movement in Mexico and was directed toward a large, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse public. By contrast, the first works he created in New York were easel paintings that focused on the city itself and were aimed at a discerning American market rather than the wider public. As he would argue in his 1929 manifesto, "New World, New Races and New Art," "Each new cycle [of art] . . . must yield its own production—its individual share to the common good." For Orozco, "the architecture of Manhattan" was the most apparent "new value" of his time.

Despite his stated appreciation for modern urban architecture, Orozco's early New York paintings do not glorify the skyscrapers that drew the attention of so many American artists, especially the so-called precisionists, who accentuated the city's clean lines and geometric underpinnings as viewed in clear, bright light. Instead, Orozco typically portrayed the city as dark, foreboding, and devoid of human activity, reflecting a more personal and socially critical response to his new urban milieu. He had arrived in America disheartened by the unfavorable response to a recent mural project at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, and he was lonely, lacking connections to New York's Anglo-American art circles. He later recalled, "It was December, and very cold in New York. I knew nobody, and I proposed to begin all over."

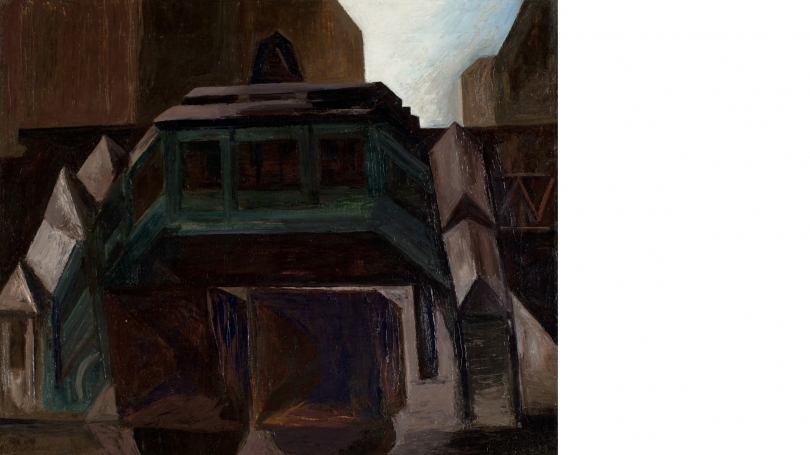

In The Elevated, Orozco transformed the picturesque Victorian trappings of a Sixth Avenue elevated train station into a shadowy, menacing structure, stripped of ornament. In a quasi-cubist manner, he reduces its outlines to essential, slightly skewed, geometric forms, broadly rendered with wide strokes of the brush. He also schematizes the structure's decorative wooden cupola to the extent that it resembles a machined armament, and the pyramidal gables of the stairway roof protrude upward like imperiling fangs. His reductive approach, combined with the station's inherent link with rapid public transit, renders it a modern, if unsettling, example of the New World's new art.