Three Perspectives

In preparation for presenting Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, the Hood Museum staff and interns conducted focus groups with current Dartmouth students to learn how they wanted to engage with the exhibition's themes. Student feedback helped to shape our presentation of, and programming for, Witness. The students particularly wanted to learn about what was happening at Dartmouth in the 1960s, and how efforts here contributed to the civil rights movement. Many people do not know that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech entitled "Towards Freedom" in Dartmouth Hall on May 23, 1962; that Malcolm X visited the College on January 26, 1965, to speak in Spaulding Auditorium, meet with students, and do a radio interview; or that the nationally-acclaimed program A Better Chance (ABC) was founded at Dartmouth in 1964.

For this Alumni Voices, three alumni each share a story of their time at Dartmouth in the 1960s. We invite you to add your voice to the dialogue when you visit the exhibition. We thank everyone who generously contributed their time and thought to shaping this aspect of the exhibition program.

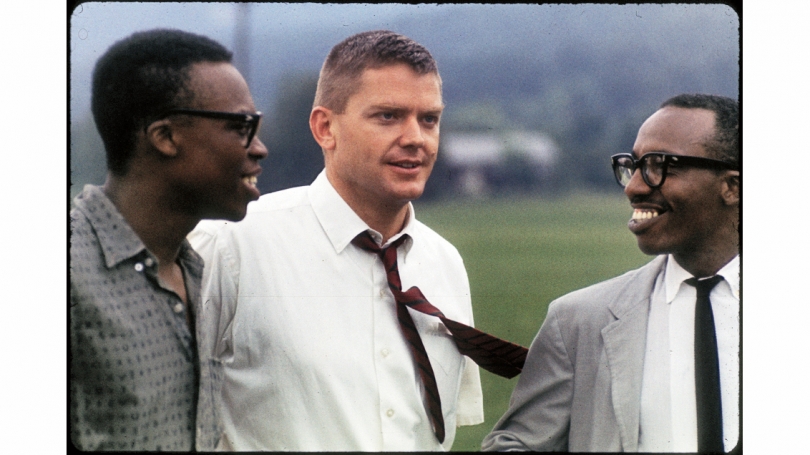

A Better Chance

It was a hot June morning in 1964. We were hungry. The six of us, four blacks, two whites, had left Birmingham, Alabama, at 6 a.m. heading north in the VOX 2 Dartmouth College car. Our first stop was the Athens, Georgia, Holiday Inn restaurant. In the large dining room, oversized menus occupied the students. When the waitress approached, instead of taking our orders she said, "We cannot serve you." To my "Why not?" she asked if I would like the name of the manager. While I was writing it on a paper napkin, he appeared. "We're not allowed to serve you. It's against the law. If the government [Civil Rights Act] makes me, then we'll have to do it. Now, you have to leave." The dining room fell silent.

On the curb outside, arms raised, fists clenched, tears streaming down his face, thirteen-year-old William Burns shouted, "Someday we'll throw them out!" The teacher within me, struggling for an apt response, said something like, "That's not the answer." At the height of the civil rights movement, we were all struggling for answers. William and fifty-four other talented students from across the country were headed for Dartmouth and A Better Chance, the revolutionary program launched by Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey in 1964.

The previous summer, President Dickey and other college and university presidents had received a personal letter from President Kennedy seeking their help "in solving the grave civil rights problems faced by this Nation." Dartmouth's role would be a summer program to assist the students' transition from home to boarding school, and Dickey asked me to develop and lead the program. He said, "We should not promise too much. Why don't we just call it A Better Chance? Give these youngsters a better chance to succeed in their preparatory schools."

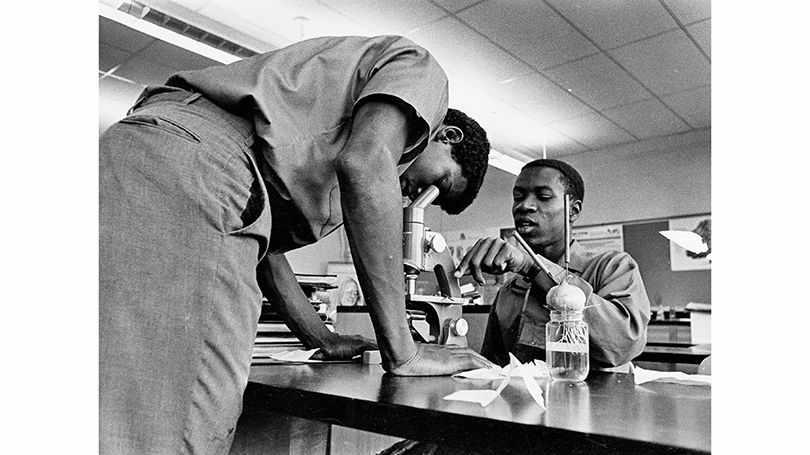

In July 1964, fifty-five thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds stepped off the busses in Hanover and into the unknown. The stakes were high. Their admission and financial aid at preparatory school was contingent upon satisfactory progress at Dartmouth. If we failed, there might not be a future ABC. Forty-nine of those students entered private schools that September and all forty-nine finished in June. They demonstrated that they could compete with the brightest of their more privileged classmates, paving the way for the 14,000 who followed.

Subsequently, under the aegis of the Tucker Foundation, Tom Mikula launched thirty-six ABC public school programs across the country, two of which helped address one of ABC's early failures—high attrition for many of the ABC Native American students in private school settings. With a grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, ABC public school residences were established in White River Junction and Woodstock, Vermont. Dartmouth President John Kemeny later commented that the ABC public school initiative accelerated his pledge that Dartmouth would make good on its historic commitment to Native American students.

Why is this important? Because fifty years later, American education continues to be starkly unequal, especially for those from poverty. Affirmative action deliberations make clear the continuing challenges for those most at risk. At the outset, ABC was a bold experimental program that took the long view and changed many lives dramatically. In my pantheon of ABC heroes there will ever be a special place for the first students and their families—for the courage and perseverance with which they faced the unknown. One hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation, ABC students and privileged white Americans gave one another a better chance.

Charles Dey '52

Associate Dean of the College, 1960–67 Director, Project ABC, 1963–66

Dean Emeritus, William Jewett Tucker Foundation, 1967–73

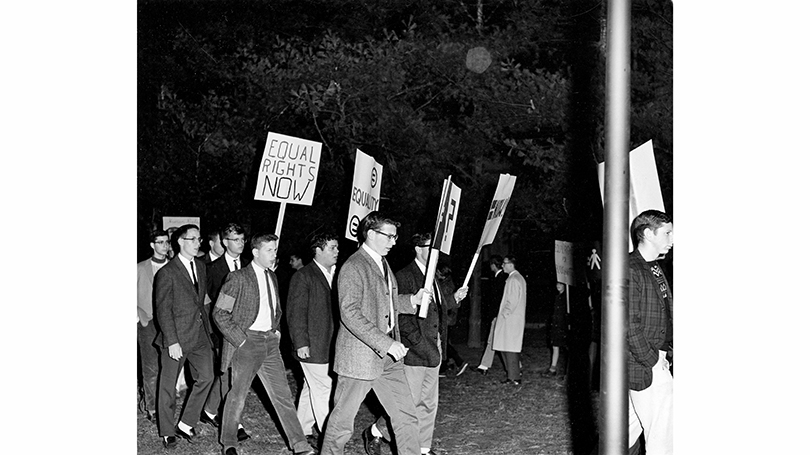

The Wallace Riot, 1967

On May 3, 1967, Governor C. George Wallace of Alabama, the iconic Southern segregationist and would-be presidential candidate, was impolitely interrupted and upbraided during a campaign speech to 1,300 Dartmouth students. That evening's event was later christened "The Wallace Riot."

By the mid-1960s, many legal barriers to full civil rights for African Americans had been dismantled through the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and countless other smaller legal and legislative victories. Nonetheless, Americans remained ambivalent and deeply divided by race and about racial issues. Chief among the defenders of segregation was Governor Wallace, who promised when gaining the governor's seat in Alabama in 1963, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever," and remained true to his word.

In November 1963, when Wallace spoke at Dartmouth as part of his first presidential bid, there were no more than six black students on campus. A small student picket line was breached without incident followed by a two-hour speech that reportedly drew twenty-seven rounds of applause. Wallace let all know that he was duly flattered.

The setting would be quite different four years later. In the 1967 presidential primary run up, Governor Wallace chose to reprise his campus tour. Black students at Dartmouth now numbered about fifty. The Afro-American Society, organized a year earlier, made plans.

The events on the evening of May 3, 1967, at Wallace's Webster Hall address played out quickly. Two groups of strategically seated black students protested loudly as Wallace began his talk. They were escorted from the Hall. Then surprisingly, a Colby Junior College professor led another group on a measured charge towards the podium. The governor withdrew from the stage as this second protest was dispersed. Wallace then finished his talk. Reportedly, there were a few applauses but the audience was mostly silent and unconvinced.

Outside, Wallace found a crowd of five hundred students encircling his car, and that is when "the riot" began. For a full fifteen minutes, the spontaneously assembled students jostled and rocked Wallace's car. Police reportedly swung billy clubs, but I never saw one. Wallace said the next day, "I was never frightened," but to a Princeton student audience a week later, he commended the orderliness of the crowd of 2,600 (with 100 security officers on hand) and remarked, "I was almost killed up at Dartmouth."

Though a southern racist had been routed from the campus, Dartmouth administrators did not see this as a proud day for the College. News of the near riot flashed across pages of the national press, from the Christian Science Monitor to the LA Times. Editorials were uniformly negative, and most of the journalistic coverage was judgmental in tone. Dean Thaddeus Seymour hastened to publish a lengthy apology. President Dickey followed with a short statement blaming "a few irresponsibles." Later, he would say to Dartmouth black students privately that he understood their passion but disagreed with their methods.

For black students, it was a proud moment. A symbol of racial intolerance and white supremacy had been firmly rebuked. The preface to a 1967 Civil Rights Reader notes, "In a racist culture, bigotry is ingested with our pablum. We would be foolish to expect it can be readily exorcised. . . . We must be prepared for a fair amount of social upheaval."

The Dartmouth students' actions, however raucous and impolite, I count among the many acts of reverential defiance to further the goals of the civil rights movement.

Forrester "Woody" Lee '68

President, Afro-American Society, 1966, 1967

Dartmouth and America, 1964–65

Dartmouth is a traditional institution that has nurtured the transformation of those traditions. We are on the cusp of retrieving the ways in which Dartmouth responded to the political and social challenges of the 1960s. Foremost among them was reforming a security state apparatus steeped in Cold War "fight any war" mentalities, the persistence of Jim Crow practices a century after the Civil War, and communities locked in poverty without educational escape ladders.

By my junior year at Dartmouth, 1963–64, I had been inducted into a lifelong career as a scholar-activist. Many of my fellow students remained oblivious to the swirling national and global challenges, or were opposed to the disruptions they represented. The locus of consciousness-raising and activism for me was the Dartmouth Christian Union (DCU) under the guidance of Rev. George Kalbfleish. It was in the DCU that my cohort encountered contemporary American progressive thought, for example, in issues of I.F. Stone Weekly and visits to campus by activists in civil rights and anti-poverty, anti-apartheid, and anti-war struggles.

There were three specific initiatives in which I was involved during 1963–64: the formation of the Negro Applications Encouragement Program (NAEP), the Valley Tutorial Program (VTP), and the A Better Chance (ABC) Program. I served in the latter as a resident tutor during its founding summer. Both the NAEP and the VTP were initiatives of the DCU. They involved Dartmouth students visiting high schools in their home areas to encourage applications from black and other inner-city youths, and providing tutorial lessons to school- children in the Upper Valley. What particularly characterized progressive activism at Dartmouth was the opportunity to engage in practical initiatives on behalf of the various causes.

The United States was experiencing great foment during this period in the form of demonstrations against the Indochina wars, mass protests for civil rights, and myriad other upheavals. Under President Lyndon Johnson, the federal government responded with the War on Poverty and Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Bill of 1965. It took another decade of war and destruction before American soldiers were forced out of Vietnam, one of the few decisive military defeats in the country's history. There is much work to be done retrieving the history of student activism at Dartmouth during the 1960s. We were not oriented to recording events in print, photography, and video formats. It would surprise many to learn how little documentation exists, for example, of Malcolm X's visit to campus to give a lecture on February 13, 1965. Despite the leading role I played in helping arrange that event, my only memoir is a personal letter from the African American leader confirming arrangements for his visit. A systematic effort to gather material items and oral memories, in conjunction with the Blacks@Dartmouth project, must therefore be launched.

In addition to the small number of student activists, there were administrators and faculty members who saw the need for major policy changes in government and educational institutions. Their support contributed to the constructive nature of our activism. We didn't devote much time to tilting against the structures of traditional Dartmouth. Instead, we built our own and cultivated our own ideals, values, and relationships. Today, it is necessary that Dartmouth embrace more fully those who planted the seeds of its transformation to become more representative of an ever more diverse American society. We used to heartily sing, "Lest the old traditions fail." But some traditions must fail, such as the exclusion of women and the use of the Indian symbol, while others must evolve, such as the previous non-recruitment of racial minorities. Today, Dartmouth is challenged to ask which among its current institutions and practices must be reduced or eliminated and which must be renewed and strengthened. A better understanding of the journey traveled would contribute to this vital exercise.

Richard Joseph '65

John Evans Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University

Related Exhibitions

- Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties

- Reflections in Black: Smithsonian African American Photography: Art and Activism

Related Stories

- Hood Quarterly, Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties

- Hood Quarterly, "Alumni Voices: Crishuana Williams '12"

- Publication: The Temple Murals: The Life of Malcolm X