NEELY MCNULTY, Hood Foundation Curator of Education

Hood Quarterly, spring 2024

In her now classic 2010 book The Participatory Museum, Nina Simon asks, "How can cultural institutions reconnect with the public and demonstrate their value and relevance in contemporary life?" It starts, she argues, when visitors actively engage as cultural participants rather than remain simply passive consumers.

pg.8-9_5th-graders_20240103-hood-437-2-2.jpg

Simon defines the participatory museum as one where audiences can create, share, and connect with each other around content. Well- designed participation is a strategy that addresses specific and common questions museums face. How do we encourage personal investment in our museums? How can we offer platforms to build community in which visitors can exchange ideas and connect with each other in our galleries even when we are not there to facilitate conversations? How can we demonstrate that we prioritize sharing multiple perspectives and stories? How can we give people opportunities to express themselves creatively and contribute to the content of the museum? Lastly, museums can be intense. How can we provide places to rest and refuel?

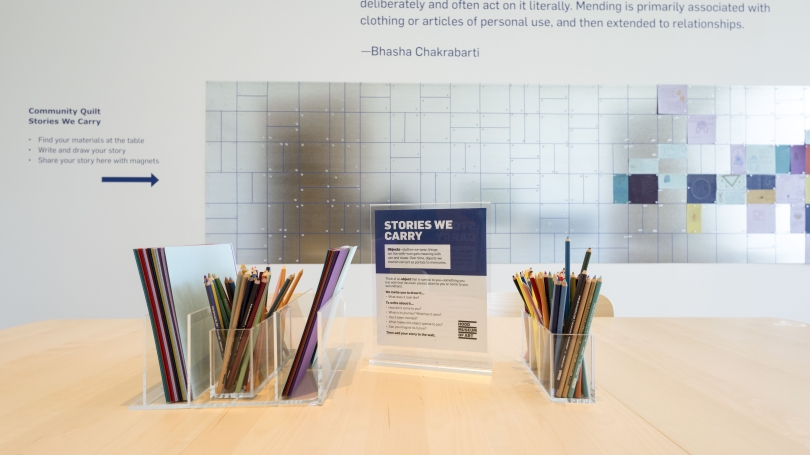

These questions directed the planning and design of Make Space, an opt-in activity space for all that was located last fall and winter in Engles Gallery, which was installed with a sofa for socializing and two tables for making. The activity offered in this space, called Stories We Carry, took inspiration from Bhasha Chakrabarti's quilted work It's a Blue World, featured in an adjacent gallery. Chakrabarti's work considers the global histories of the plant indigo from its earliest uses to the present day. It also invites us to think about how Chakrabarti uses mending as a metaphor for relationship repair and growth.

pg.8-9_5th_graders2_20240103-hood-321-2-2.jpg

In the Make Space gallery, one wall featured information about indigo, the dye used to make Chakrabarti's quilt. A second wall featured a prompt in which visitors were invited to consider how objects we cherish can accrue meaning through use and even act as portals to memories. Visitors were encouraged to think about an object from their lives that had been passed down or come to them secondhand. Using colored pencils and paper to draw that object and write its story, they could consider questions such as the following: How did it come to you? What makes this object special? Has it been mended? What is its journey; what has it seen? They could add their completed drawings and stories to a long metal wall, gridded with tape to suggest a quilt. With magnets, visitors moved drawings around and actively changed the composition week in and week out.

Within five months, visitors of all ages had added nearly 1,000 drawings and stories, representing a range of divergent perspectives and experiences like these:

(A drawing of a bottle holding soil) Ancestral soil from the adobe house my grandfather built during the Guatemalan civil war. The small building housed my childhood kitchen. Memories of raw tomatoes, running with the dogs, and playing in the corn fields. All gone after the earthquake. I carry it with me to remember where I am from and as a thank you to the hands that provided sustenance in it.

pg.8-9_teachers_rs96446_img_6500-2.jpg

(A drawing of a bike) My friend MR.SURLY took me over mountains, thru mud, to class, to work, to the beach, to soccer, with friends or alone, but always forward, and always back home.

(A face drawn in several shades) My pigment has been passed down generation to generation for centuries. Its journey began in Africa and has settled in the US today. It has seen everything, but its journey is far from OVER.

As we plan forward at the Hood Museum, what can we learn from the success of this experiment? Participation is more likely when activities are scaffolded so that people understand expectations and feel motivated to engage with confidence. The simple prompts in this activity encouraged multidirectional content experiences across all audience sectors, if visitors opted in. Structured around a theme, the prompts functioned as a set of constraints that focused participation and motivated an authentic personal response. Visitors could read different perspectives, wonder about others' experiences, creatively express their ideas, and make meaning on their own terms—all outcomes that align with our values as an institution that centers art and people in teaching and learning.