Native American Art and Material Culture

"We found a way to work through this and to continue to thrive, really." - Jami Powell

Read about how associate curator and lecturer Jami Powell adapted to virtual teaching with an innovative course model.

In mid-March, Dartmouth announced that all spring term classes would be held remotely due to the rapid outbreak of COVID-19. As members of an institution that prides itself on in-person connection and deep engagement, Dartmouth professors and students alike had to adapt to virtual education.

Jami Powell, associate curator for Native American Art at the Hood Museum and lecturer in Native American Studies at Dartmouth, energetically met the challenges of remote teaching with an innovative course structure.

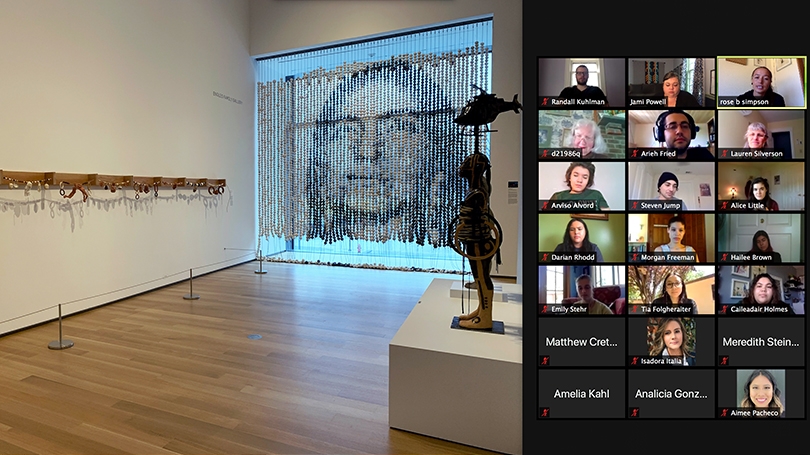

Powell had designed the course "Native American Art and Material Culture" with the intention of centering object-based learning experiences in the Hood Museum of Art's galleries and Bernstein Center for Object Study. As the first Native American art history course taught exclusively in the museum, Powell's class attracted students from all grades and several different majors.

Recognizing that her initial plans were no longer feasible, Powell decided to use the remote format to her advantage in the (virtual) classroom. In a recent interview about her course, she said: "Even though we had all of these limitations that made it really difficult and we weren't able to be in the museum and work with objects, it also opened up incredible possibilities."

In order to restructure her museum-based course into a virtual platform, Powell made a significant shift "from focusing on the materiality of the artwork to focusing on art as a social practice and community-based practice." Each week, Powell invited leading Indigenous artists from across the country to meet with her students over Zoom. Throughout the spring term, ten Indigenous artists met the class to discuss their motivations, practices, and recent work, before engaging in open conversation with the students.

In an email exchange, student Hailee Brown '20 wrote of the course: "It is one thing to read about an artist's work but Professor Powell gave us the opportunity to converse with the artists directly. As the artists were all Indigenous, this gave them their own autonomy to speak about their work and stories, which historically has not been an option for Native American artists."

In addition to interacting with more guest speakers than would have been feasible in a typical term, the class had the unintentional benefit of witnessing what Powell called "human moments." Meeting over Zoom, students caught a glimpse into the real lives of artists, getting behind-the-scenes visits into their studios, glances at artwork-in-progress, and the chance to meet some of their families.

One of Powell's favorite "human moments" from the artist conversation series was when Ian Kuali'i was discussing a new project and realized that he had an unfinished example on hand to hold up to his screen and share with the class.

Powell also highlighted that students had the chance to learn about how these artists, many of whom are also social activists, were coping with and responding to the challenges arising during the spring term. For example, Artist Will Wilson, who participated in a residency at the Hood in January and has an exhibition on view at the museum, began using the tools in his studio to create face shields designed by the Georgia Tech Rapid Response remote PPE production initiative.

Student Tia Folgheraiter '21 wrote of her experience: "I greatly appreciated attending the artist conversations throughout the weeks as it was inspiring to hear about various Indigenous artists using their work as a political message to advocate for greater sovereignty and rights."

Rather than presenting her students with a linear narrative of Native American art, Powell structured her course into thematic groupings such as "stereotypes," "feminisms," "art & ecology," or "colonialism & critique." The goal of her thematic course structure was to "[allow] students the space to see the way that these ideas are layered in really complicated ways and the entanglements that are embedded within the art world, museums, and universities."

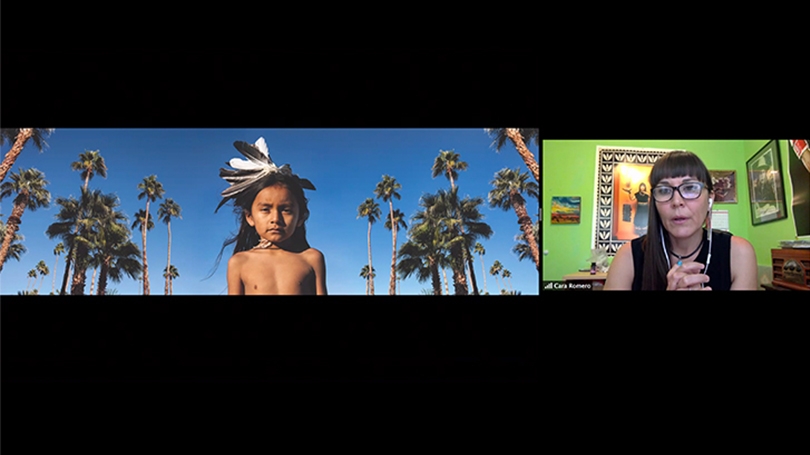

While Maeve McBride '20, particularly enjoyed the conversation with artist Courtney M. Leonard because it "underscored the relationship between art and the environment," Tia Folgheraiter '21 appreciated "listening to Cara Romero's artist conversation because she expressed Indigenous relationships to the land."

Powell encourages her students to be active participants in class and share their unique perspectives in discussions. "I really like to invite students to bring their own experiences and understandings of the world into what they learn about the material in the class. How do we form personal connections to objects? Or how do we relate to the objects we are studying? How do we bring that into our understanding of the material and our own lives and shared experiences?"

To Powell, one of the greatest outcomes of her course was the confirmation that "Humans are really resilient. We found a way to work through this and to continue to thrive, really. I was so impressed with my students and the thoughtful participation that took place in our course."

Written by Devon Mifflin '21, Digital Engagement Project Assistant