Hood Quarterly, spring/summer 2010

Mary Desjardins, Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies, Dartmouth College

American films made during the "golden age" of Hollywood, the era when the film studios produced almost five hundred films a year, have held a place of esteem in art museums, college film societies, and academic departments for almost a century. Interest in the artistic and historical values of the work produced by Hollywood studio photographers, however, goes back only a few decades. Made in Hollywood: Photographs from the John Kobal Foundation, at the Hood from July 10 to September 12, showcases the Hollywood photography collection of the individual who is perhaps most responsible for sparking that interest among scholars, art lovers, and movie fans. John Kobal (1940–1991), a film fan since his childhood viewing of a Rita Hayworth movie in post-war, Allied-occupied Austria, started his career in writing about film in the 1960s as a freelance journalist for BBC radio. His interviews with actors took him to New York and Hollywood. While his contemporaries treated the economic decline and cultural transition of Hollywood at this time with cynicism or through a nostalgic reverence for the past, Kobal's fascination centered on what could be made of the change. For him, Hollywood's most valuable surviving relics were the voluminous photographic collections of star portraits and film production stills that the studios, now dissolving or being absorbed by conglomerates, were giving up or even throwing away.

Kobal's collection of Hollywood star portrait photos and film production stills serves as the basis for many of his books on film history and stardom. The museum exhibitions he curated—the first major displays of Hollywood photography— inspired other collectors and fueled a growing interest in charting a popular history of twentieth-century American culture through the fantasies and ideals created out of Hollywood and its stars. Kobal's authority as a historian and passion as a collector-curator arise from his sense that the value of these photographs is only partially derived from the part they played in a particular economic system of mass cultural production, or their ability to imprint on the public's imagination definitive images of particular stars. Instead, or moreover, as he states in his book The Art of the Great Hollywood Portrait Photographers, "These images belong to an experience." He goes on to argue that "the finest among them create an emotional empathy akin to that found in a bar of music, a line of poetry, or a canvas filled with color." His study favorably compares Hollywood portrait photography to the works of the greatest portrait painters, whereas his delightful book of interviews, People Will Talk, reveals and records the experiences of stars and photographers in goldenage Hollywood.

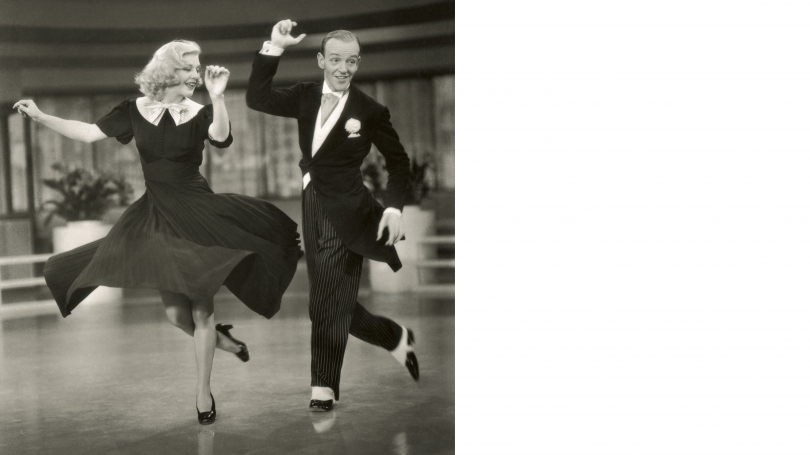

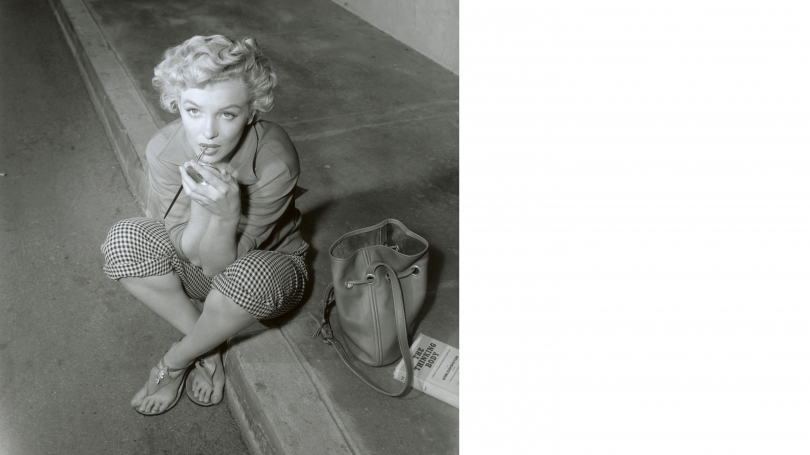

Kobal's interest in what transpired between star subjects and studio photographers is evident in his large collection of self-reflexive images of "the photo shoot," some of which are on display in the Hood exhibition. In all likelihood, these were taken either for the photographer's own portfolio or for use in the movie fan magazines so important to the studios' promotion of their films and stars. The studios' need for publicity and promotion was the primary reason for the prodigious output—about 250 to 300 negatives per day—that they demanded from their staff photographers. These photographers specialized in creating one of three kinds of photographs: (1) stills from the film set (shot after the last take of an important scene or shot of a film, such as the still taken by John Miehle on the set of Swing Time, or the amazing photo attributed to Milton Brown of Lillian Gish on the set of The Wind) for use on lobby cards, posters, and ad copy; (2) portraits (usually shot in the photographer's own "gallery" on the lot); and (3) publicity shots (often taken off-site at a star's home or other location).

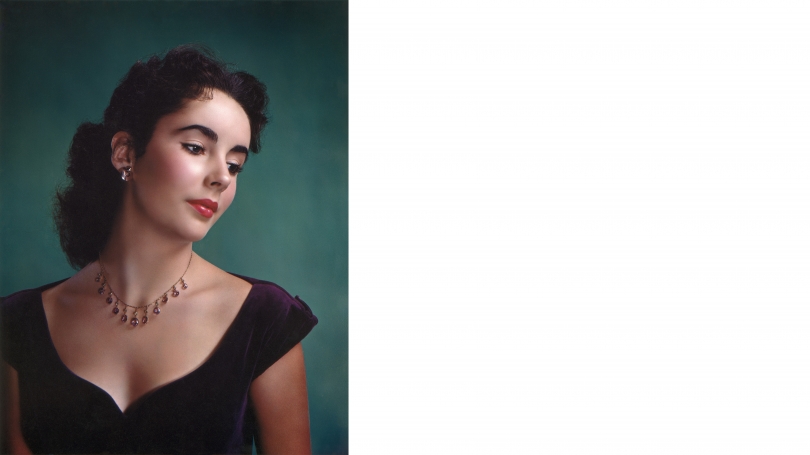

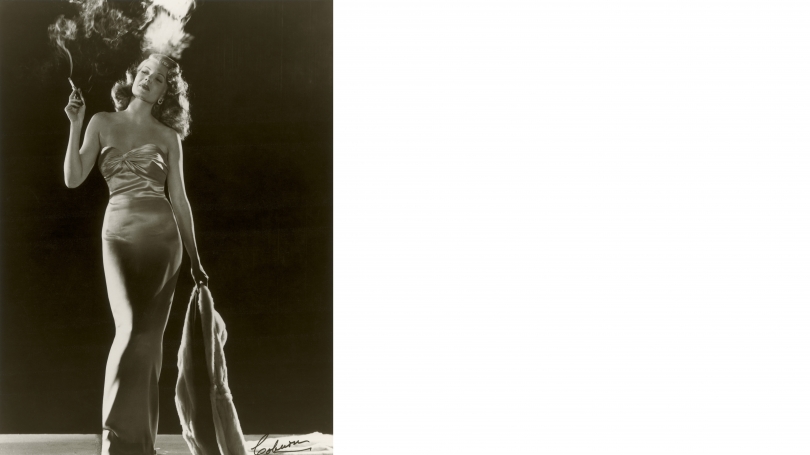

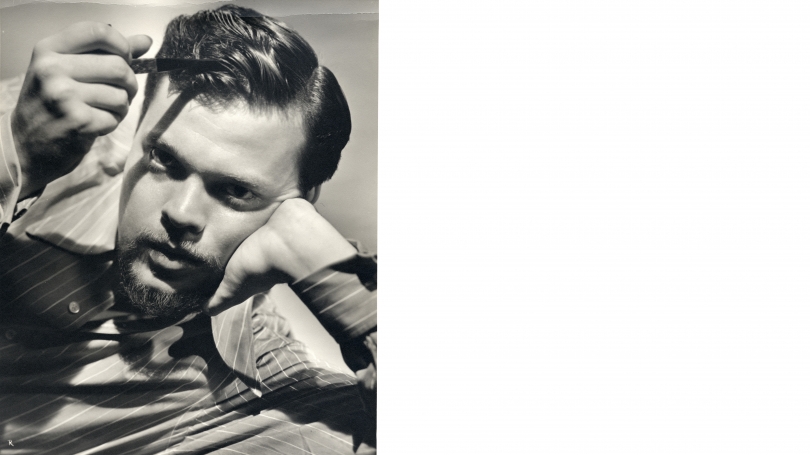

The portrait was the most important vehicle for the promotion of the studios' most valuable assets—their stars. It was used in the development of a persona that, to be sellable, had to project both a recognizable "type" and the special qualities that made the star unique. This star persona was rarely fixed overnight, although Ernest A. Bachrach's 1940 collaboration with Orson Welles on a portrait created at the very moment the star-director arrived at RKO suggests a genius that had been preordained before he had even directed or acted in his debut film (Citizen Kane) at the studio. A comparison of Gene Korman's 1939 photo of Rita Cansino (subsequently Hayworth) to Robert Coburn's 1946 photo of her for Gilda demonstrates the possibility inherent in the studio publicity shot. While the former presents the charming but not exceptional qualities of an as yet typical Hollywood starlet, the latter, one of the most reproduced star portraits of the studio era, reveals a perfect storm of artistry from Hayworth the performer, Coburn the photographer, and Jean-Louis the costume designer. While the breathtaking silk gown worn by the actress in both film and photo hugs every curve of the star's body, Coburn's lighting scheme, suggesting an environment of light and shadow that is at once ethereal and material, complements Hayworth's insouciant head tilt and casual bodily stance in creating a living, breathing woman who could nonetheless be conjured in the fantasies and dreams of her fans as a being who was not of this world.

Robert Dance, curator of the Hood exhibition, author of Glamour of the Gods: Photographs from the John Kobal Foundation, and co-author of a study of photographer Ruth Harriet Louise, notes that Kobal's work as collector, curator, and author between the late 1960s and 1991 resuscitated the careers of forgotten photographers and reintroduced them and their star subjects to a new generation of film enthusiasts. Made in Hollywood: Photographs from the John Kobal Foundation promises to do that and more—to introduce the life's work of John Kobal to a new generation of art lovers and film fans.

Related Exhibitions

- Made in Hollywood: Photographs from the John Kobal Foundation

- Stacey Steers: Night Hunter House

- Follow the Money: Andy Warhol's American Dream