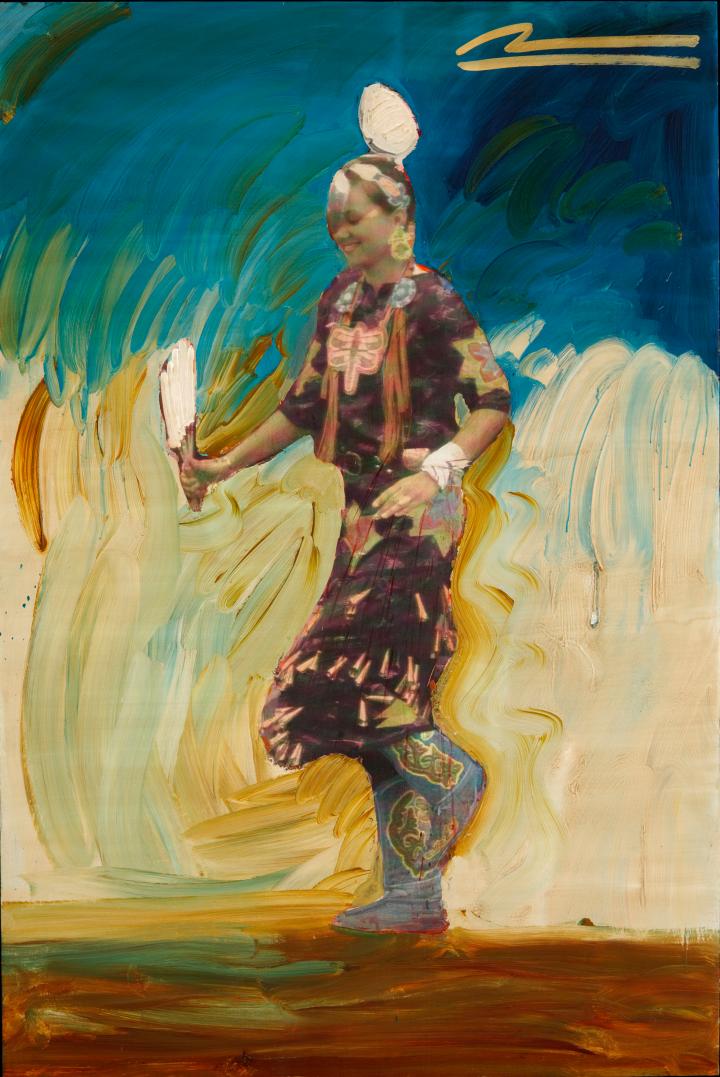

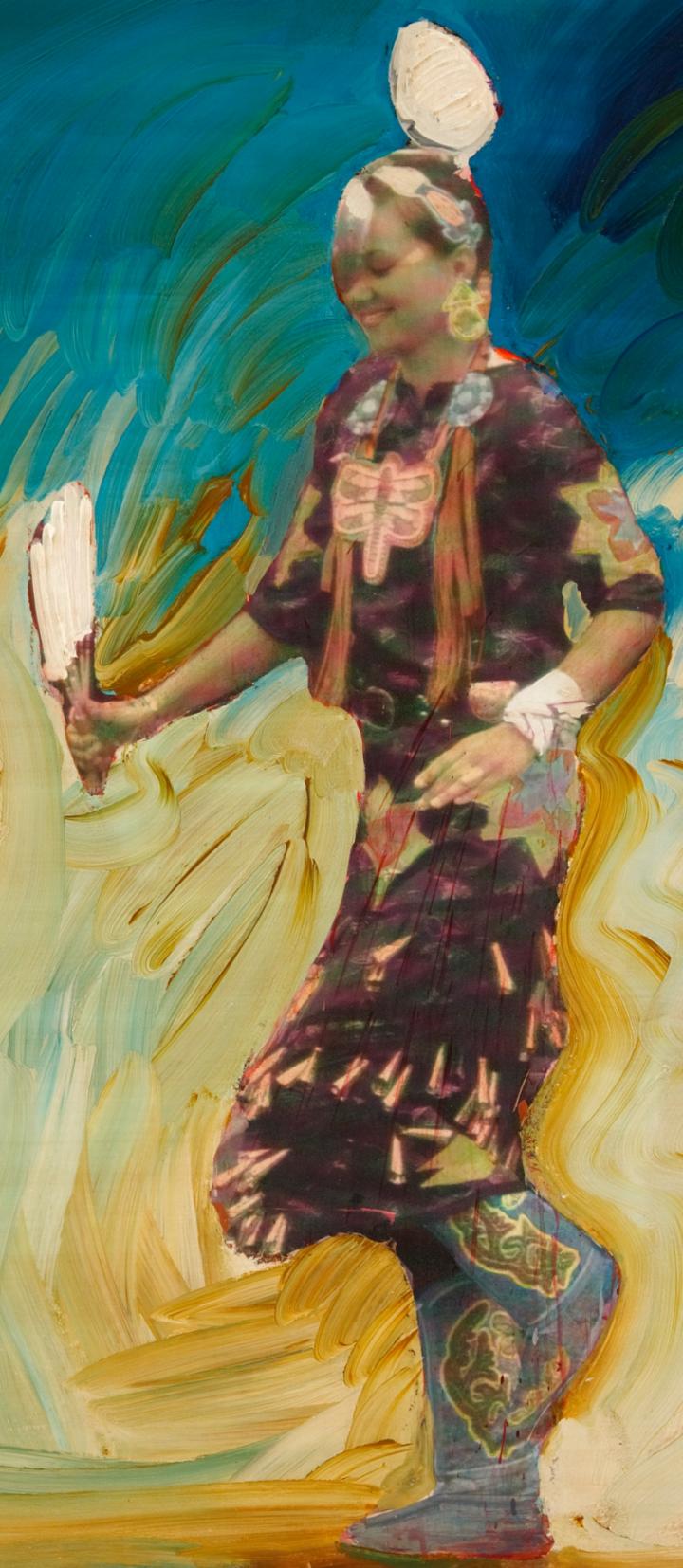

Mateo Romero, "Bloom" (Kayla Gebeck), 2009, photo transfer and acrylic paint on panel. Purchased through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W'18 Fund; 2010.35.5.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see. Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you notice when you look at this image?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work with questions such as:

* What do you notice about the figure? Her expression?

* Her pose?

* Her dress?

* What is she holding in her hand?

* What do you notice about the background? the colors? the brushstrokes?

* What materials and processes do you see in this work?

* How would you describe the artist’s style?

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work. For instance:

* What process do you think the artist used to create this work? Where did he start? What did he do next?

* What does the figure appear to be doing? What is it about the artist's style that adds dynamism to the scene?

* Do you think this is a portrait of an individual or a painting of a type of person?

* What is the artist's attitude toward this person?

* What is the overall mood of this piece?

After each response, always ask, "How do you know?" or "How can you tell?" and have students point out the visual evidence in the work of art to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

At the end of this document, you will find some background information on this object. Read it or paraphrase it for your students.

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* What do you think this artist is trying to communicate about the Native American tradition of dance with this work?

* How has Mateo Romero conveyed his feelings in his work?

* In what ways does this work represent continuity in Native American tradition and culture? In what ways is it innovative and new?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Do you think this work of art is successful and well done? Why or why not?

This fifth stage can also encompass one’s individual response to a work of art. One’s response can be much more personal and subjective than one’s assessment.

* Do you like this work of art? Does it move you?

* Are the ideas in this image powerful to you? Do they relate to your own life?

Background Information

Mateo Romero, Cochiti Pueblo, born 1966

"Bloom" (Kayla Gebeck), 2009

Photo transfer and acrylic paint on panel

Purchased through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W'18 Fund; 2010.35.5

Mateo Romero was born in Berkeley, California. His father, grandmother, and brother are also artists. He attended Dartmouth College and the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and he earned an MFA degree in printmaking at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Today, he is not only a successful painter but also a writer, curator, and educator.

In 2009, the Hood Museum of Art commissioned Romero to create ten paintings inspired by the Dartmouth Pow-Wow of that year. He traveled to Dartmouth and took photographs of dancers in tribal regalia. He then transferred a selection of the photos to panel and painted over and around the images. In these works, Romero emphasizes the textured surface and the expressionistic quality of the brushstrokes to suggest rhythm and movement. This dynamic surface blurs the boundary between foreground and background so that the dancer becomes an iconic figure floating in space.

Dartmouth's annual Pow-Wow began in the 1970s as a small gathering and has grown to an event that attracts upwards of 1,500 people from all over the country. It is an opportunity for members of the Dartmouth community and the Upper Valley to see and participate in Native American culture from many different tribes and traditions. For Native American students at Dartmouth (NAD), the Pow-Wow serves as a cultural expression that reinforces their identity, regardless of tribal background.

Quote from the artist:

"Dartmouth College has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. Although I graduated in 1989 and have since been part of numerous academic programs, being a part of the Dartmouth family has been a tangible and real aspect of my life as a mature artist. As my first art dealer in Santa Fe, David Rettig, Class of 1975, once commented, we are part of the Dartmouth Tribe now.

The Dartmouth Pow-Wow Suite has given me the opportunity to come full circle in my artistic life as an active participant in the vibrancy of the Dartmouth community. It is with tremendous joy and energy that we created these portraits of current Dartmouth students and alumni.

We began by photographing the Dartmouth Pow-Wow 2009. Photographic images are selected, enlarged, transferred to panel, and painted on with acrylic. Tar glaze is applied at the end for surface luminosity and atmosphere. The end result is a collision between photographic portraiture and abstract expressionist paint handling. There is a palpable tension between figure and ground, literal and abstract, portraiture and the nostalgic quality of action painting.

In many Native communities the dance holds a powerful, central place in the structure of the worldview. Dances are, at different times, social, amorous, honoring, ceremonial, spiritual. In the Tewa Pueblos in northern New Mexico, dancers entering the houses of their relatives say, "We Dance for Life." It is in this spirit that I offer these paintings to the audience. My hope is that the works transcend the limits of ethnic culture and address the audience on a human level.

This painting, one of the series, features Kayla Gebeck, Dartmouth Class of 2012, Red Lake Anishinaabe, and is entitled, 'Bloom.'

Kayla Gebeck was an Occom Scholar during 2008–2009. She was awarded a First-Year Summer Research Project Grant through the First-Year Deans Office and an Office of Undergraduate Research Fellowship to design a research project that examined Hawaiian language revitalization efforts with an eye to applying these to her own Ojibwemowin language work in Minnesota. During her senior year, 2011–2012, Kayla will be co-president of Native Americans at Dartmouth."

Kayla Gebeck writes:

"The Jingle dress originated from the Anishinaabe people. Although it was originally used for ceremonial purposes and represents strength and healing, the Jingle dress has played an important role in my life. Dancing from the time I could walk, I embraced all of the components of the dance; the history, significance, symbolic role, and even the process of making the dress and associated regalia. With this in mind, when I dance, I dance for my family and my elders, giving strength and pride to my people. For this reason, it is even more important for me to continue sharing my dance with the Dartmouth community."