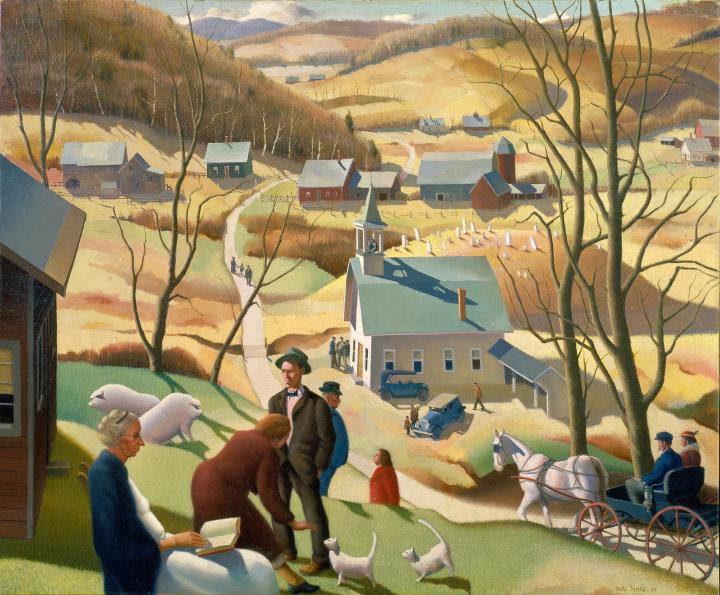

Paul Sample, Beaver Meadow, 1939, oil on canvas. Gift of the artist, Class of 1920, in memory of his brother, Donald M. Sample, Class of 1921; P.943.126.1.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see. Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you see or notice when you look at this painting?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work with questions such as:

* What do you notice about the setting?

* The land?

* The various buildings?

* The road?

* What do you notice about the figures in the foreground?

* Their clothing?

* Their body language?

* Their expressions?

* What do you notice about the figures in the middleground?

* In the background?

* What types of transportation are pictured in this scene?

* What animals has the artist chosen to include? What do they have in common?

Finally, look carefully at the way the artist composed the entire painting.

* What do you notice about the colors?

- The shapes?

- The lines?

* How has the artist organized the space?

* Overall, what words would you use to describe this painting and the artist’s style?

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work. For instance:

* Where in the world do you think this scene might be taking place?

- When?

- During what season?

- On what day of the week?

* Where would you need to be standing in order to see the scene from this point of view? How does your eye move over the scene from this vantage point?

* How would you describe the relationships between the people in this painting? Between the people and the land?

* Does this style of painting remind you of other works of art or images you have seen?

* Would you describe the artist's style as realistic? Abstract? Or both? Why?

After each response, always ask, "How do you know?" or "How can you tell?" so that students will look to the work of art for visual evidence to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

At the end of this document, you will find some background information on this object. Read it or paraphrase it for your students.

When you have finished sharing the information, consider the following:

* Does this information reinforce what you observed and deduced on your own?

* Did it mention anything you did not see or think about previously? If so, what?

* How would your experience of this painting have been different if you read the background information first?

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* Images that celebrated different regions of America were quite popular during the 1930's. Why might that have been?

* Why do you think Sample chose a style so like early American folk art for this New England scene?

* What does Paul Sample seem to be saying about Beaver Meadow and the people who live there? Is this a positive, romanticized image of New England? In what ways? Does it also seem critical? How?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Do you think this painting is successful and well done? Why or why not?

This fifth stage can also encompass one’s response to a work of art. One’s response can be much more personal and subjective than one’s assessment.

* Do you like this work of art? Does it move you?

* Are the ideas in this image still relevant today?

Background Information

Paul Sample, American, 1896–1974

Beaver Meadow, 1939

Oil on canvas

Gift of the artist, Class of 1920, in memory of his brother, Donald M. Sample, Class of 1921; P.943.126.1

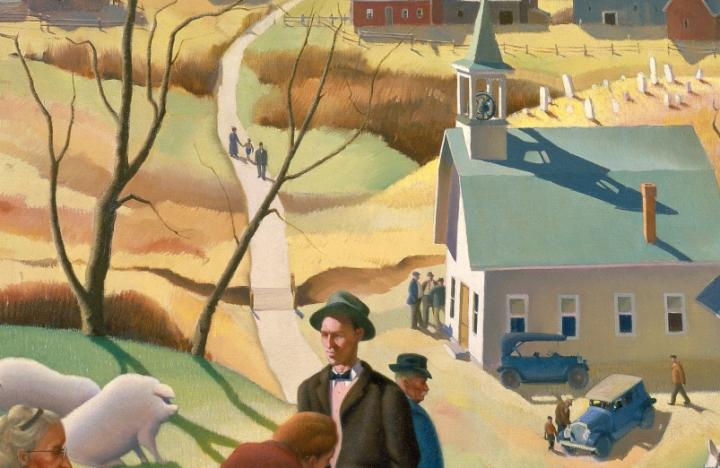

While Paul Sample was artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College from 1938 to 1962, he lived primarily across the Connecticut River in Norwich, Vermont. Depicting the small settlement known as Beaver Meadow within the rural township of Norwich, this painting features the hamlet's church and several of its known residents. Beaver Meadow eloquently expresses many of the aesthetics and ideals of the regionalist movement of the 1930s. Regionalist artists like Sample, Grant Wood, and Thomas Hart Benton celebrated the distinctive topography and manners associated with different regions of the country. They were especially drawn to rural communities whose traditional customs were perceived to be threatened by such homogenizing forces as big business and new forms of transportation and communication. Keenly aware of the widespread hardships that so many people experienced during the Great Depression, Regionalist artists aimed to boost the spirits of the average American by depicting local subjects in an appealing, simplified, highly legible style. In Beaver Meadow, for instance, Sample created a lean, decorative composition that evokes popular illustration, caricature, and American folk art traditions.

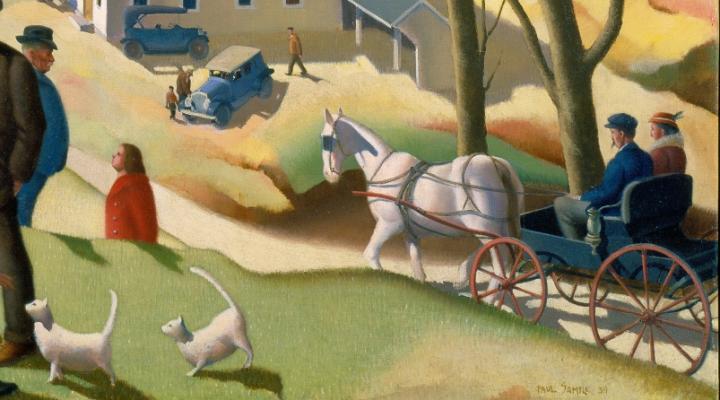

In Beaver Meadow Sample hints at tensions between tradition and change in rural Vermont, and offers a mixed portrayal of his new home in New England. On the one hand, the painting celebrates qualities associated with a stereotypical Vermont village: the harmonious relationships between humans and nature, as reflected in the tidy fields and farm buildings nestled in the hills, and among the members of this apparently idyllic settlement, whose sense of community is strengthened through weekly worship. Yet the picture also includes such harbingers of "progress" as the automobiles parked next to the church's empty carriage stalls. Representing the customs of an older generation, a horse-drawn carriage conveys an elderly couple toward the church, their more formal garb contrasting with that of the more casually dressed men and boy situated near the cars. Sample also evokes an undercurrent of unease, and even suspicion in the composition, suggested by the rigidity of the figures in the foreground and their disconnected gazes. A rather schoolmarmish figure, identified in a preliminary sketch as "Mrs. Roberts" (her pose taken directly from James McNeill Whistler's famous portrait of his mother), is absorbed in her reading.

Her male counterpart, a rather gaunt New England Yankee type, stands looking absently downward. Further beyond, we see two rotund figures facing one another, but set apart in space. At the far left a pair of plump pigs face opposing directions, further drawing attention to the odd poses of their human counterparts. Presumably Sample's view of his new Vermont surroundings and neighbors was more complex than the all-out boosterism generally associated with the regionalist aesthetic.