JOHN R. STOMBERG, Virginia Rice Kelsey 1961s Director

Hood Quarterly, summer 2023

I FELT MORE AND MORE THAT THE DRAWING SHOULD COME FROM WHAT THE SHAPES OF THE COLORS ARE; RATHER THAN, "I AM ARRANGING THIS WITH LINES OR CONFINEMENTS OR PATTERNS." AND I DO VERY MUCH BELIEVE IN DRAWING, ESPECIALLY WHEN IT DOESN'T SHOW AS DRAWING . . . WHEN I TALK ABOUT DRAWING, I MEAN "HOW ARE YOU GETTING YOUR SPACE," AND NOT WHERE IS THE PENCIL GOING.

—HELEN FRANKENTHALER, 1965

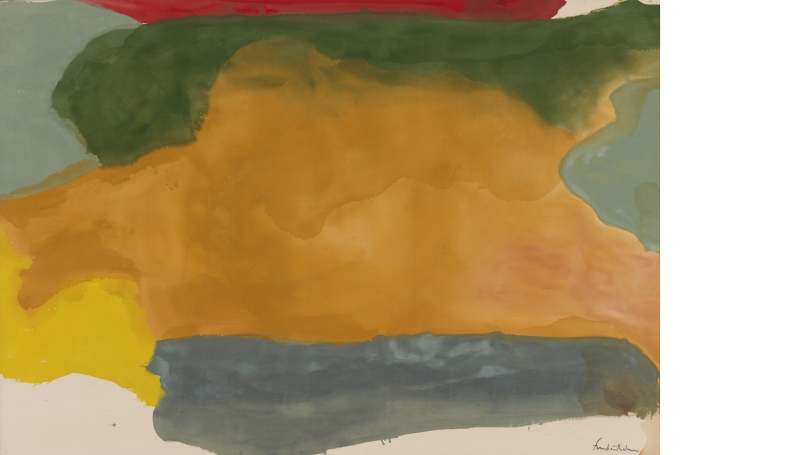

Frankenthaler pushed the boundaries between abstraction and representation in her paintings of this era. With Inlet she painted broad horizontal swaths of color that gesture toward the seascape she suggests in her title. At the time, she was spending her summers in the small oceanfront town of Provincetown, Massachusetts. Though remote, Provincetown has long been a place attractive to artists who respond to the qualities of light. As the town occupies the very tip of the peninsula, the sea surrounds it on three sides, creating weather conditions not unlike an island. Further, the significant low tide reveals sand flats that extend miles out into the Cape Cod Bay. While this work would be equally powerful without benefit of the suggestive title, the artist clearly wanted to add a reference to the world outside the edges of her canvas. In this way, she enriches our experience of the work and allows Inlet to exist within the context of both allusion and illusion.

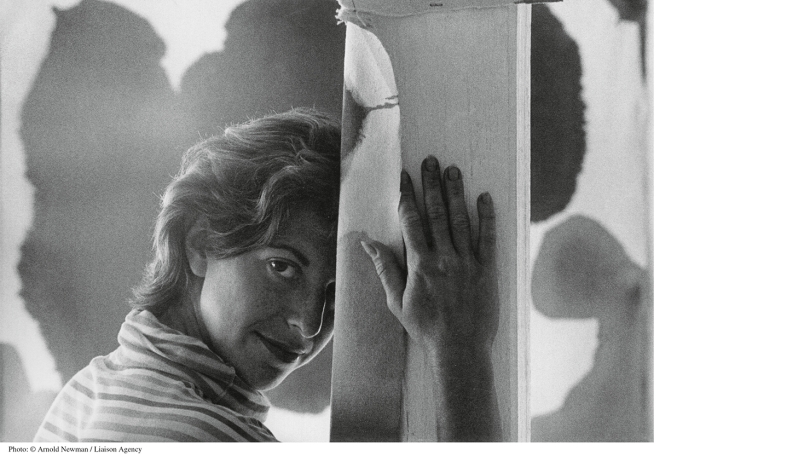

Pulling away from the angst-ridden, self-revelatory mode of Abstract Expressionism, Helen Frankenthaler charted a new course for her own art and for American painting in general. After graduating from Bennington College in 1949, she moved to New York, where by 1952 she had established a reputation for herself as the generator of a new approach to painting. Referred to as "soak and stain," her technique involved pouring thinned oil paint directly onto unprimed canvas laying on the floor. (She later replaced oil and thinner with acrylic paint in paintings, including Inlet, to avoid conservation issues.) By carefully lifting the canvas, she could encourage the paint to flow as she directed it, all the time allowing it to function somewhat independent of her wishes. The style that emerged from her efforts strongly influenced generations of painters starting with artists such as Morris Lewis and Ken Noland.

Beyond the stunning visual impact of her work, her paintings were (and are) celebrated for the robust theoretical framework in which they operate. Postwar painting, especially in New York, gained its early critical definition from Clement Greenberg (with whom Frankenthaler had a five-year personal relationship). He wrote of the need for painters to turn their backs on representation and to focus on paint, texture, edges, color, and line—the inherent qualities of the medium. Frankenthaler's pioneering technique fused those ideals with a further step: she allowed the viscosity of her paint to help determine the look of the finished work. By soaking the unprimed canvas, the paint and canvas became one—not a painting on canvas, but a new object entirely. These ideas caught the imaginations of a new generation of painters, originally dubbed Post Painterly by Greenberg but soon categorized as Color Field.

Her influence also can be found in the later work of her husband Robert Motherwell (1915– 1991), to whom she was married from 1958 to 1971, and particularly his "Open Series." During the years they were together, Provincetown loomed large for them, both as a destination for summer escapes and as a center for their social life. The Hood Museum collection has a Motherwell that was completed the year the couple married. It is titled simply Chambre D'Amour.

With a major work by Frankenthaler in the collection, the Hood is now better able to represent the breadth of truly amazing artists at work during this period. For a variety of reasons, many of the best painters of the period have eluded their just recognition because past scholars focused only on a small number of mostly male exemplars in their studies. Inlet derives from a moment in Frankenthaler's career when she moved boldly out of her early experimentation of the 1950s and into her signature approach. It is a painting of importance to the Hood Museum for the critical chapter it adds to our story of American painting, just as it occupies a distinct place in art history for its daring blend of theoretical advance and visual indulgence.