ELIZABETH RICE MATTISON, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Academic Programming

ASHLEY OFFILL, Associate Curator of Collections

Hood Quarterly, spring 2023

Over the course of the past year, curators at the Hood Museum of Art have forged new connections with Dartmouth scientists to bring fresh perspectives to the permanent collection. While conservation departments in larger museums conduct scientific testing (called technical analysis) on collections, the Hood Museum does not have conservators on site. Nevertheless, as an academic museum situated within a premier research university opportunities for scientific cooperation abound. In uniting scientists and curators, the museum has begun to better understand the physical properties of artworks, find traces of human interactions with the objects in their original contexts, and teach in new and different ways. Collaborations have emerged from an effort to answer specific questions raised by scientists and by the museum; together, we are integrating the Hood Museum into the academic life of the Dartmouth community.

The museum's scientific partnerships began in winter 2022 when the Hood Museum acquired a medieval reliquary bust. Made to house a relic—a piece of a saint venerated in Christian devotion— the bust posed an essential question: Was anything still inside? This query brought us to the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center and Geisel School of Medicine where Dr. P. Jack Hoopes, professor of surgery and radiation oncology, and Dr. David Gladstone, professor of medicine, used computerized tomography (CT) scanning to examine the structure and contents of the reliquary, now empty. The success of this project prompted us to seek additional campus relationships to understand other objects in our collection from a technical perspective. (Read more about scanning the reliquary on the Hood Museum's blog Meanwhile at the Museum.)

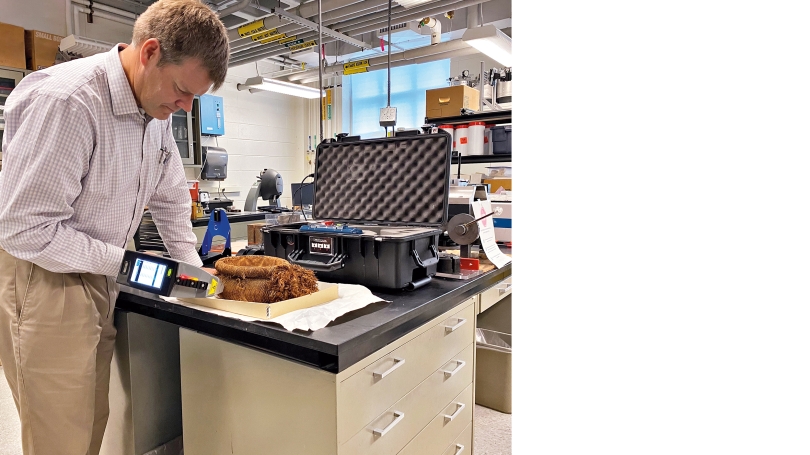

While investigation of the reliquary focused on its interior, another recent project examined the surface of a Gitxaala headdress, which will be repatriated in 2023. Staff at the Hood Museum suspected that the headdress, made of cedar bark and cloth, may be coated with harmful chemicals used as preservatives in anthropological collections in the nineteenth century. We wanted to determine if substances like arsenic were present, which could be transferred if the headdress were reactivated or worn in a ceremony. Zachary Miller, cultural heritage fellow, contacted Douglas Van Citters, associate professor of engineering, to run XRF (X-ray florescence) testing. The process sends X-rays into a material, knocking electrons from their molecular orbits. When the electron falls back into orbit, the sensor detects unique signatures of each element present. Testing took place in September 2022 in the engineering lab with museum staff members Zachary Miller, Ashley Offill, and Nichelle Gaumont. Professor Van Citters tested four areas of the headdress for sixty seconds each. Prior to testing, the machine was calibrated with a soil sample containing arsenic to ensure that the tests registered the proper elements. Ultimately, the scans detected arsenic, copper, titanium, manganese, zinc, mercury, and lead. While the arsenic level was low compared to nineteenthcentury taxidermy, the arsenic and heavy metals like lead and mercury indicate that the headdress likely underwent preservation treatment in the past. This information is vital for the Hood Museum to pass on to the Gitxaala community when the museum returns the headdress.

Other collaborations have resulted from exhibitions. In spring 2023, Nathaniel Dominy, Charles Hansen Professor of Anthropology, will organize a teaching exhibition in conjunction with his course, "The Human Spectrum." Professor Dominy's show focuses on the cross-cultural use of ochre, a clay-derived pigment ranging from earthy reds to dusty yellows. It is present in diverse objects in the museum's collection, such as an ancient Egyptian stele, Nasca pottery, and contemporary Aboriginal Australian bark painting. To better understand color differences as they relate to geographic location, Professor Dominy measured the wavelength distribution of the objects with a PR-750 Spectrascan telespectroradiometer. Importantly, the testing does not damage the objects: the machine operates passively by recording incoming light. With this device, Professor Dominy measured the specific wavelengths of the different ochre pigments present from around the world. We will process his data to create a graph of the color fluctuations as they relate to origin and time period, allowing students and visitors alike to understand the varieties of ochre pigmentation.

Additionally, the impetus for scientific study comes from Dartmouth students. Professor Jiajing Wang, assistant professor of anthropology, brought her class, "Archaeology of Food," to the Bernstein Center for Object Study in May 2022 to examine ancient objects used to store or process food. After closely examining an Egyptian clay vessel identified in the museum's database as a beer jar, students wanted to know why was there a hole near its base and if it truly held beer. Professor Wang followed up by requesting to conduct noninvasive residue testing on the jar's interior. In October, Professor Wang and a student from the class returned to gather samples from the "beer jar" and comparable vessels. Using a pipette, they saturated a small interior area with distilled water to loosen any residue. Using an electric toothbrush, they agitated the wet surface to release particles. Professor Wang extracted the resulting suspension for testing. While final analysis is still pending, initial results show that at least one vessel indeed held beer. The hole was likely a later alteration, made when the jar was no longer used or transitioned to a funerary context. In addition to giving the Hood Museum more information about our collection, this testing enabled a student to gain hands-on experience with archaeological objects and methods of field testing.

In the past year, we have collaborated with five colleagues to scientifically examine our objects. A new avenue to connect with campus, these partnerships represent only the beginning of bringing science to the museum. We have recently begun a project with the Thayer School of Engineering to create 3D-printed models of objects to use in interpretive displays and to create a touch collection for visitors with low or no vision. As we look ahead, we are excited about the possibilities for further integration of the arts and sciences at Dartmouth.