HAELY CHANG, Jane and Raphael Bernstein Associate Curator of East Asian Art

Hood Quarterly, spring 2024

Since arriving at the Hood Museum of Art in the fall of 2023, I have spent my days slowly picking through the Asian art collection, looking for moments of inspiration and vision. What does this collection have to offer? What can I offer to it? As the first curator of East Asian art at the Hood Museum, I have the special opportunity to provide the love and care this collection deserves, and I will start this quest by shining some light on where it all began.

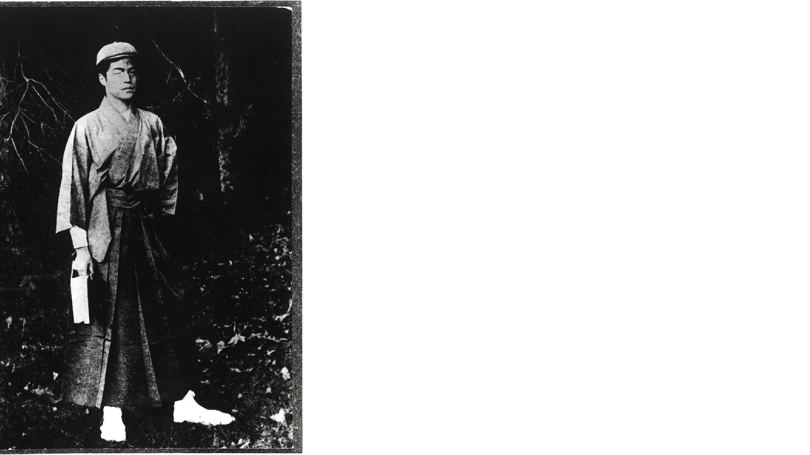

What are the earliest Asian art objects to enter the College's collection? In 1899, Reverend James H. Pettee, Class of 1873, gifted a group of Japanese and Ainu objects to the Butterfield Ethnographical Museum of the Department of Sociology at Dartmouth.1 During his service as a missionary in Okayama, Japan, from 1879 to 1919, Pettee acquired the objects he brought to Dartmouth when he returned to Hanover in 1898 for the reunion of his class.2 Forty-eight of these works remain at the Hood Museum, including everyday objects such as a tobacco box, snowshoes, and a kettle, along with pieces of Edo period armor and 19th-century Ainu attire. The collection reflects Pettee's aspiration to comprehend Japan through its cultural objects, acquired from every corner of the country.

figure_1_pettee_high-res.jpg

Curiosity, however, was never the sole impetus for Pettee's collecting. In the same year as his donation, Pettee contributed a short piece entitled "Old Dartmouth and New Japan" to the student newspaper, The Dartmouth. After briefly introducing Japan as a nation that Americans "had barely discovered upon the map of the world," he described how Dartmouth alumni, including himself, were contributing to the "onward, upward movement of that progressive nation [Japan]" as missionaries and educators.3

Pettee's enthusiasm adds another layer to our understanding of his donation to Dartmouth. By offering the objects as an opportunity for ethnographical study, Pettee aimed to incorporate Japan into the intellectual map of the College community. That map, however, operated as a field of division rather than inclusion in the era of Western imperialism, which constantly measured Asia's progression vis-à-vis the West. The desire to define others presumes an unequal power relationship, as Pettee's words indicate.

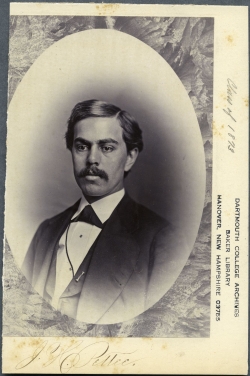

In 1899, when Pettee gifted his Japanese collections and writing, Asakawa Kan'ichi graduated from Dartmouth with honors in German. As the first student from East Asia in the College's history, Asakawa went on to earn a Ph.D. in history at Yale University, where he later served as a professor of Japanese history.4 After his immersion in philosophy, religion, and aesthetics at Dartmouth, Asakawa thought of himself as a global rather than Japanese intellectual. Always careful not to circumscribe his scholarly viewpoint according to his nationality and race, the young Asakawa aimed to "stand on universal ground and ask human questions and live out the destiny of mankind" through his study.5 His interest lay in locating Japanese culture and philosophy less in the arena of competition with Western modernity than in the wider intellectual world being created by diverse voices. To achieve this, Asakawa sought to apply his knowledge of Japan and his fields of study to the moral and social questions of his time. His scholarship therefore oscillated between Japan's past and America's present, distancing him from the progressive futurity cultivated by his contemporaries.

It remains unclear whether Asakawa was aware of the arrival of Pettee's collections at Dartmouth. Nonetheless, I find myself peering through Asakawa's eyes when I look at Pettee's gifts and in that way refrain from utilizing those objects to try to define what Japan was. Many conversations can emerge from these collections concerning our coexistence with nature, the settler colonization of Ainu lands, and the Western gaze toward Japan, for example. The question is how to extract wisdom with which to explore our own time through objects created in the near or distant past—the work of curatorship that I share with Asakawa and envision at the Hood Museum of Art.

Notes

1. "Addition Made to Butterfield Ethnographical Collection," Dartmouth Alumni Magazine 12, no. 3 (January 1920): 597.

2. "Class Reports: Class of 1873," Dartmouth Alumni Magazine 12, no. 5 (March 1920): 720–21.

3. James H. Pettee, "Memoranda Alumnorum: Old Dartmouth and New Japan," The Dartmouth 20, no. 17 (February 3, 1899): 299 and 302.

4. "Kan-ichi Asakawa," Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University Deceased During the Year 1948–1949, Series 46, no. 1 (January 1, 1950): 141–42.

5. Letter from Asakawa Kan'ichi to his friend Will, 6 August 1899, Microfilm, MS 40; HM 201, Box 1, Reel 1U, Kan'ichi Asakawa Papers 1895–1906, Series 1. Correspondence, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Special Collections, New Haven, CT. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/archival_ objects/1181825. The last name of the recipient of this letter is not mentioned, but it is thought to be Willard Isaac Hyatt, Class of 1899, who resided in Spragueville, NY, the location to which this letter was addressed.