Homecoming will be on view July 22, 2023 – May 25, 2024.

The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, presents Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art from July 22, 2023, to May 25, 2024, featuring over 75 works drawn from the museum's collection of African and African diaspora art. Emphasizing the role of women artists and feminine aesthetics in crafting African and African diaspora art histories, this exhibition surveys themes of home, kinship, motherhood, femininity, and intimacy in both historic and contemporary works.

"I began imagining plans for Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art in early 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period that coincided with an uptick in conditions of and activist responses to antiBlack racism and xenophobia," explains Alexandra Thomas, curatorial research associate at the Hood Museum of Art and curator of this exhibition. "I hope the exhibition encourages everyone to discuss the kindred themes of domesticity and kinship in their everyday lives. Who performs the labor that builds and sustains our communities and how is that reflected in the visual and material culture of the world around us?"

Artists have creatively engaged with the domestic sphere and related themes for centuries. For example, a 19th-century grass broom made by an unidentified Zulu artist is associated with the labor of the Black South African women who craft and use them for domestic work while also evoking the pan-African religious practice of spiritual cleansing. Homecoming affirms craftmaking as artmaking and domestic and spiritual work as creative work—undoing patriarchal definitions that seek to separate and hierarchize these categories. The exhibition will include women's cloth garments, sculptures symbolizing motherhood and fertility, intimate representations of figures within domestic interiors, dolls and dollhouses, household tools, and more.

In many ways, Homecoming speaks to our current historical moment. We have mourned and survived through the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and begun to understand its lasting impact on our lives. Remote work and its gendered division of labor, the loss of certain forms of physical togetherness to social distancing necessities, and, of course, the premature loss of loved ones, are all part of a moment in which domesticity, kinship, and intimacy are widespread in the public discourse.

Examples of works in the exhibition:

rs9706_2017-55_001-20_cr-scr.jpg

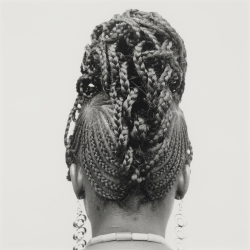

Abebe, by Nigerian photographer J. D. 'Okhai Ojeikere, celebrates the beauty and pride of Black women's hairstyles that are widely popular in Africa and throughout the diaspora. Ojeikere has documented hundreds of these highly stylized coiffures to serve as portraits of Black women's beauty culture. Practitioners of this art form are subjected to meticulous evaluation based on the length, style, and shape of their braids, and it requires years of practice to perfect one's technique.

rs18308_p-984-39-3_001-scr.jpg

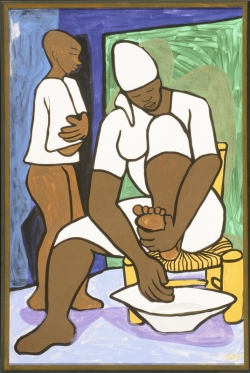

Mother and Son, by Haitian artist Roland Dorcély, depicts a mother and her child, dressed in stark white clothing, who are washing their feet in an image perhaps evocative of Haitian Vodou. In Haiti, Vodou practitioners often wear white, symbolizing purity, at ceremonies. Haitian Vodou is a blend of West African Vodun spirituality and Roman Catholicism, and the act of cleansing one's feet in a basin might allude to the Christian ritual of feet washing.

rs26974_t-2003-6_001-19_cr-scr.jpg

Untitled (Adire Quilt) by Nigerian artist Nike Davies-Okundaye is one of the many indigo textiles on display. Its geometric designs and varied shades of blue are characteristic of the West African art form. In southwestern Nigeria, Yoruba women have long created adire—indigo-dyed fabrics that are known to the world for their dazzling colors and intricate patterns. Historically, the dye used for these garments was sourced from local plants, but industrialized forms of the dye are now readily available, too. Generations of Yoruba women maintain the tradition of designing and wearing these indigo textiles.

rs5936_2008-8-4_001-scr.jpg

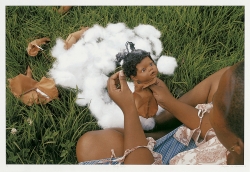

The Baby Doll series of photographs by South African artist Senzeni Marasela reveals how artmaking can be entangled with the emotional processing of traumatic histories. A Black baby doll, shown against bright green grass, is captured as it unravels—or, perhaps, as it is sewn together. It is ambiguous, powerfully so, as the artist uses the image to gesture toward the uncertainty and violence of being a Black child growing up under South African apartheid. This photograph is from a series of twelve, each of which pictures the doll at a point of destruction or construction.

rs2374_167-6-24038_001-16-scr.jpg

Masks from the African continent offer a strong political and aesthetic component to the themes of domesticity and kinship. One example in Homecoming is a Gelede mask representing Osanyin, the orisha (deity) of herbal medicines, surrounded by four disciples, which was made by an unidentified Yoruba artist. At Gelede festivals, Yoruba men perform a masquerade in honor of the significant roles women play in the community as mothers, traders, elders, and ancestors. Blue pigment, either natural indigo or an industrialized dye called washing blue, is applied to many Yoruba sculptures, like those on this mask. The blue expresses coolness, purity, discretion, and composure. It is often associated with water deities, such as Yemoja, who is the goddess of rivers and is known as a patron deity of pregnant women.

Works in Homecoming will rotate throughout the year it is on view to meet the conservation needs of the various textiles, paintings, and works on paper.

Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art is organized by the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, and generously supported by the William B. Jaffe and Evelyn A. Hall Fund.