ASHLEY OFFILL, Associate Curator of Collections

Hood Quarterly, summer 2022

In many ways, being a collections curator is like being a detective. A key part of my work as the recently hired associate curator of collections at the Hood Museum of Art involves the big picture of the museum's collection: supporting its strengths as well as identifying areas for further research by staff at the Hood, faculty at Dartmouth, and external collaborators; activating works of art that have been in storage, through both teaching and exhibitions; and assessing needs related to conservation and collections care and developing plans to facilitate the safety and use of the collection in conversation with our registrars and preparators. In the day to day, I serve as a conduit between the objects in the collection and the people who engage with them.

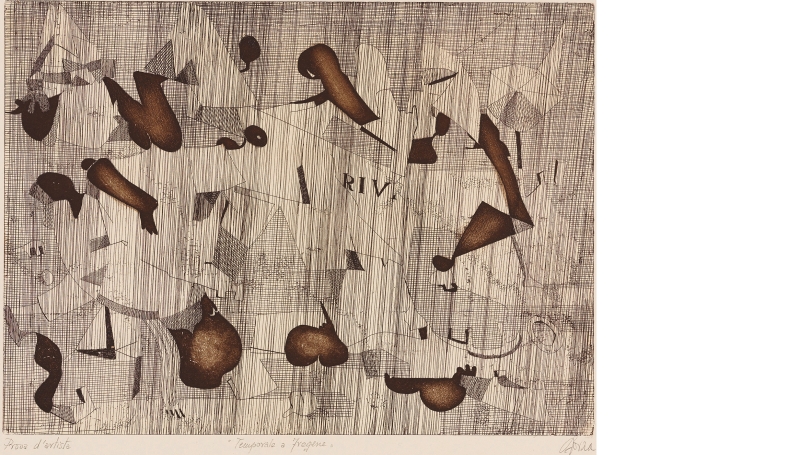

Here, I want to share two case studies that explore how focused work with objects in the collection contributes to ongoing discovery and engagement. A recent mystery involves an etching in the Hood Museum's collection titled Temporale a Fregene (Thunderstorm in Fregene). Fregene is a small town near Rome, and the print is attributed to an artist named Giorgio Sforza. However, this print was brought to my attention because a coworker could not find any trace of an artist named Giorgio Sforza and thought that I might have more luck, given my background in Italian art.

I began my search with the print itself, looking at characteristics of the style as well as the information written in pencil on the sheet, which reads "Prova d'artista" (artist's proof) at the bottom left, "Temporale a Fregene" at center, and bears a loopy signature at bottom right. Next, I turned to the records kept at the museum, both in our digital database and our paper files. Unfortunately, information from both sources was limited, and while I could decipher "Sforza" in the signature if I looked for it, there were no records of where the first name "Giorgio" came from.

I made use of the Getty's Union List of Artist Names to search for Sforza and many other possible names I deciphered within the signature. With no luck there, I conducted a broad examination of Italian printmakers in the mid-twentieth century, hoping to find a visual comparison, which was also unsuccessful. While it can be hard to leave a mystery unsolved, at times the best thing to do is step away and come back with fresh eyes. In a collection of over 65,000 works of art, however, there is always something else to investigate.

While reference photographs are a valuable tool, many things can only be gauged through physically examining a work of art. In February, I worked with Elizabeth Rice Mattison and Lauren Silverson to bring a sixteenth-century Flemish tapestry out from storage. The tapestry was likely produced in a workshop in Oudenaarde, a town in present-day Belgium particularly known for its production of verdure, tapestries with lush landscapes rendered in vivid greens and blues. While tapestries were an expensive luxury object in Europe during the medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods, their popularity waned in the modern era, which may be part of the reason why this tapestry, simply titled Hunting Scene, had been unviewed and unexhibited since 1979.

When we unrolled the tapestry, we inspected the condition of the textile, looking for any damage the weaving may have sustained in its centuries-long life, such as holes or tears, fading from light exposure, or insect activity. Maneuvering the heavy, rolled tapestry was a challenge, but there was a sense of anticipation as we revealed the woven woolen surface that had been covered for decades. The tapestry was in wonderful condition and, struck by the impact of the tableau unfolding in the Bernstein Center for Object Study, I quickly sent an email inviting museum staff to share in the moment. More than half of the on-site staff were able to closely engage with the tapestry. Facilitating transformative encounters with works of art, like this one, is at the core of the Hood's mission, and as staff we enjoy and learn from objects in the collection alongside our audiences.

Exciting discoveries are ongoing at the Hood Museum. As I edited this essay, I ran one last internet query that revitalized the search for Giorgio Sforza: it appears that an artist by that name participated in the 3rd International Exhibition of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in 1959. Knowledge of the artist can increase our understanding of the context of the print, allowing the museum to use it more broadly in teaching and exhibitions, so research on Sforza and his print continues.

Collaboration is key at the Hood Museum of Art. Do you know anything about the print highlighted in this article or other objects in the collection? Feel free to contact Hood.Collections@dartmouth.edu as we continue to investigate and care for the works of art entrusted to the Hood Museum.