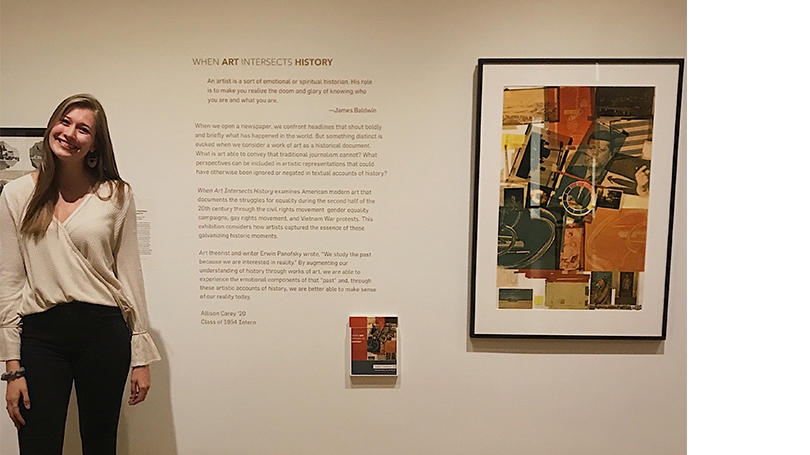

Allison Carey, Class of 1954 Intern for curatorial, talks about her experience as a Hood Senior Intern.

What does your internship at the Hood Museum entail?

As the Class of 1954 Intern, I work for Barbara, or "Bonnie," MacAdam, the American Art curator. I spend my time compiling research or drafting object labels for Bonnie's upcoming exhibitions, brainstorming hangs for future shows, and conducting research to fill out reports on newly acquired objects in the Hood's collection. What this really means is that every day "in the office" looks different. Sometimes you can find me deep in the archives doing in-depth research, while other days I am in object storage getting a close look at certain works of art.

Why were you interested in a Hood Museum internship?

I have had a few internships in museums over the past few years, and each experience was incredibly rewarding. I felt like I was a part of something special; the work I did supported a space where people could come to be inspired, learn about new perspectives, and create connections— both internally and with a greater community. Applying to work at the Hood was a no brainer: I would gain valuable experience at a renowned institution and have the unprecedented opportunity to curate my own show. But, perhaps most importantly, during this internship my contributions would be felt by a community I have a personal connection to.

What has been the most memorable moment of your internship so far?

My most memorable moment is really a compilation of moments: every Monday I check in with my supervisor, Bonnie, and we chat about our week and the work that lies ahead. This ritual conversation is always stimulating and exciting. Our discussions range from exchanging our thoughts on certain works in the collection to considering possible objects that could be included in her upcoming shows, or just to brainstorming titles for my Space for Dialogue exhibition. I learn so much from Bonnie during these weekly check-ins, and they have become one of the most valuable parts of my internship.

What is the topic of your Space for Dialogue exhibition and why did you choose it?

My Space for Dialogue show, When Art Intersects History, considers what happens when we regard a work of art as a historical document. When people ask why I study art history, I tell them that by looking at art we can understand history through a unique lens. James Baldwin summed it up nicely, stating that "An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are." Not bound by the limits and potential misappropriation of words, artists can freely explore raw emotions and present unique perspectives on the world.

In my show, I examine works of American modern art that document the history of equality during the second half of the twentieth century. The show explores how American artists have invaluably captured their perspectives on galvanizing historic moments. By contrasting certain works on view with contemporaneous excerpts from The Dartmouth, the college newspaper, I aim to consider how art provides a unique view on the past, while also demonstrating that human reality is complicated, tempered by vast differences in perspective and place. Ultimately, the show strives to augment our understanding of history through the lens of an artist, allowing viewers to better understand the humanity and emotions of the second half of the 20th century in order to make better sense of today.

What was the most surprising part of the curatorial process for your Space for Dialogue exhibition?

When I decided on a topic for my show, I thought that the most powerful works of art would be the ones that directly alluded to historical narratives. I envisioned Robert Rauschenberg's screenprint CORE being the central piece of my show: the work collages images of specific moments and figures that defined the Civil Rights Movement—it is beyond fitting for the theme of my exhibition. But after my show was installed, I was surprised to find myself most drawn to some of the smaller works of art that more subtly played into my theme. George Tooker's Half Dozen Eggs, for example, is a delicate little painting of a carton of brown and white eggs. Like CORE this painting also references the Civil Rights Movement, serving as a subtle call for desegregation. It was really surprising to see how certain artworks are transformed when they are hung on a wall. For me, the smallest piece in my show became the most powerful.

What was your first encounter with the Hood Museum?

The Hood Museum was under renovation until my junior year. Despite this, some of my art history professors still kept us connected with the collection and the staff. In Professor Coffey's class "American Century," we used the Hood's online database to familiarize ourselves with their collection of American modern art. After doing so, we broke into groups and digitally curated shows based on the Hood's collection in a website form. The process allowed us to work directly with the Hood's curators; their excitement for both the artwork and the greater institution they worked for was palpable. When the doors of the new museum finally opened a year later, it was amazing to walk through the galleries and encounter the very works I had studied for this project in person. I already felt connected to the space.

If you could borrow one object from the Hood Museum's collection to display in your home, what would it be?

If I could borrow one object it would be Fred Wilson's Ota Benga. I chose to study this sculpture for a whole term in my senior seminar with Professor Kassler-Taub. Ota Benga is both physically and symbolically layered with significance. The subject of the sculpture is Ota Benga; a prisoner of the Congo who was put on live display in the Louisiana World's Fair in 1904 as an example of a "primitive" pygmy, or a less developed "other" that was positioned in degrading comparison to the civilized West. A live cast was made of the boy, which eventually found its way in Hanover, New Hampshire in the mid-1930s. At Dartmouth, it served as a pedagogical tool, studied by students as a "pygmy." It wasn't until the early 2000s when Fred Wilson rediscovered the long-forgotten object in the Hood's collection. Wilson reclaimed the bust's dignity by wrapping a memorializing white scarf around its neck, which covers its hurtful label of "pygmy." Yet he still reminds viewers of the object's traumatic history through a harrowing inscription in the base: "I'm the one who left, and didn't come back." The combination of materials, authorship, and subject matter reframes the bust and its traumatic past, offering the individual a chance to be considered in a new light as deserving of re-consideration and respect.

I think if this sculpture was on display in my home it would serve as a crucial reminder that multiple histories—many still underrepresented—shape our past. I imagine my home would be filled with stimulating and important conversations surrounding this topic.

What five words best describe your internship experience at the Hood Museum?

Stimulating, collaboration, community, challenging, rewarding