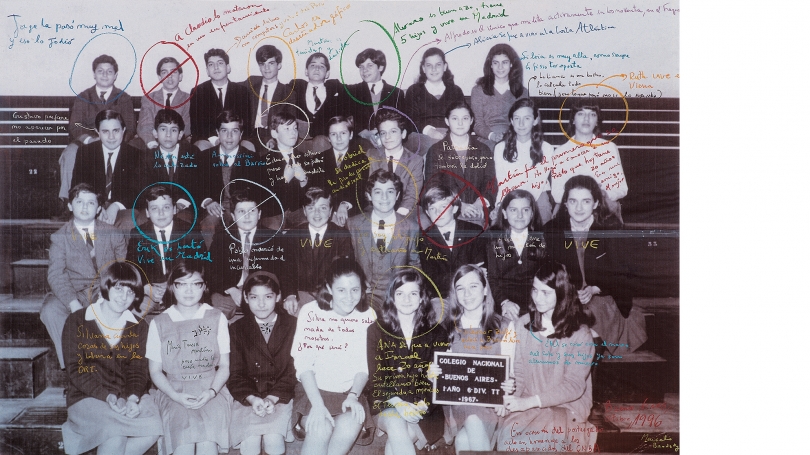

Marcelo Brodsky's La Clase begins with his own school picture of the first-year students, sixth division, of the Colegio Nacional Buenos Aires, in 1967. After his return from exile after the end of Argentina's Dirty War (1976–1983), during which his brother and many of his contemporaries were victims of political disappearance, torture, and murder, Brodsky enlarged this class photo to huge proportions.

Using the image as a platform for memory and memorialization, he reunited surviving classmates and inscribed the children's bodies with brief comments about their lives—and also about their disappearances and deaths—written in a variety of colors on the photo's surface.

"Carlos is a graphic designer" (slide 2); "Claudio was killed fighting the military in December 1975"; "Silvia does not want to know anything about us. Why would that be?" Three inscription, in colored ink, simply read "ALIVE." Some faces are circled and others, the dead, disappeared, and killed, are circled and crossed out. These cross outs, etched into the print's surface, erase individuals from the group and transmit the cold, institutional violence that affects us as viewers. But these marks convey defiance and the determination to call public attention to classmates' murders as well.

For the artist's own account of the making of this image, see this video account by filmmaker Vikki Bell.

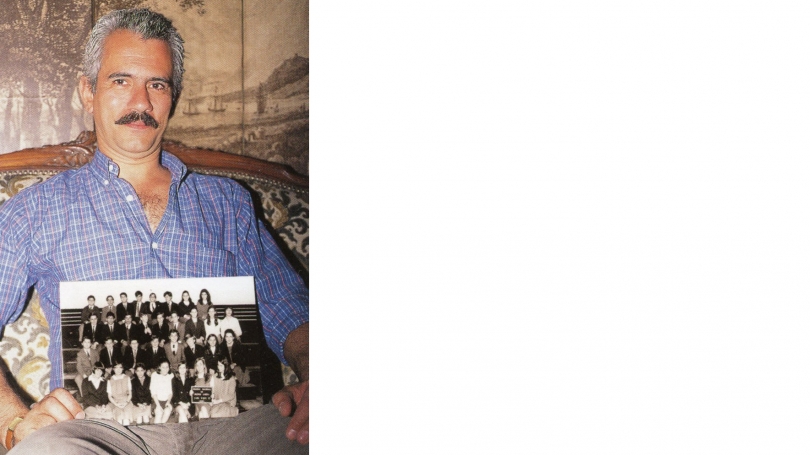

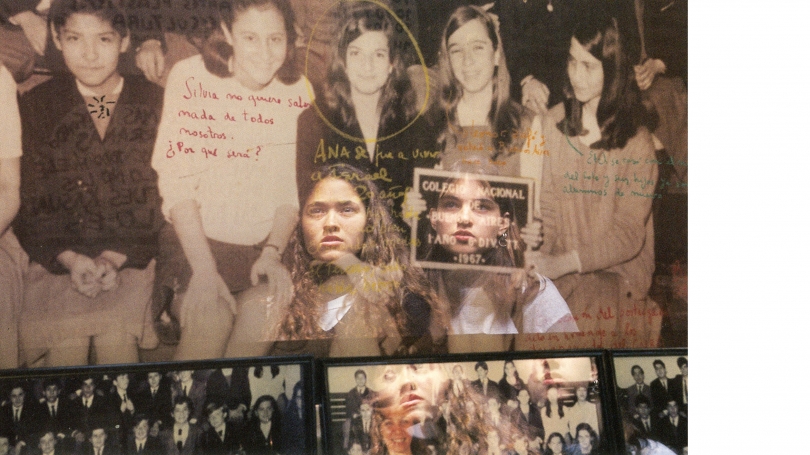

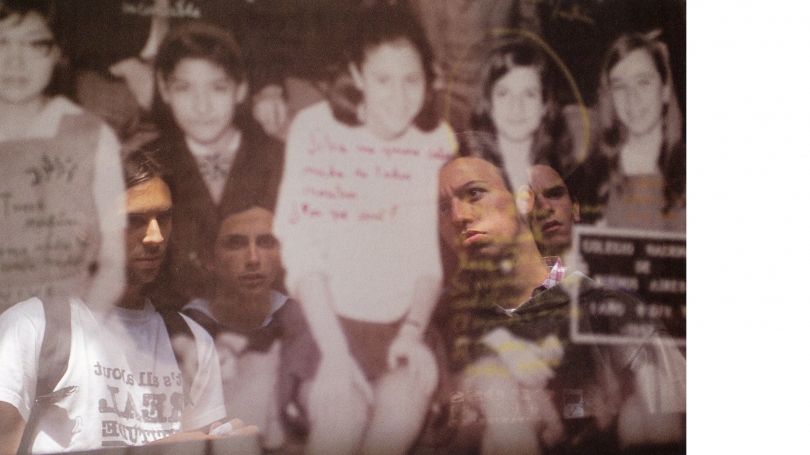

La Clase became part of a larger project, Buena Memoria (Good Memory). In its second phase, Puente de la Memoria (Memory Bridge) (slides 3 and 4), La Clase served as a catalyst for a commemoration ceremony organized by students subsequently enrolled in the school. The students engaged with Brodsky's project and with the legacies of Argentina's recent violent history.

In 2014, Marcelo Brodsky returned to La Clase, reactivating it in response to a new political crime. His "visual action" responded directly to the forced disappearance of 43 students from the Raúl Isidro Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa, Mexico, with a call for worldwide solidarity (slide 5).

The students from Ayotzinapa were on their way to a protest commemoration of the 1968 massacre of three hundred students in Mexico City's Tlatelolco neighborhood. They boarded a bus to the capital in Iguala but were immediately removed by the police. They were handed over to a local criminal organization, but then their traces were lost and remain so to this day. The precise circumstances of their disappearance are still hotly contested, but the police, the army, and the government were all implicated.

Students from across the globe sent in similar group photos to mark their solidarity with the forty-three victims. Their signs spelled out demands for justice: Somos Todos Ayotzinapa (We Are All Ayotzinapa), Verdad, Justicia (Truth, Justice), 43 Razones Para Decir Basta (43 Reasons to Say Enough), ¡Vivos se los llevaron, Vivos los queremos! (They were taken alive, we want them back alive!).

As a collective project, the visual action allowed participating students to assume agency in their self-representation. The images they produced join school images made elsewhere in acts of civil disobedience, as new student movements grow in our own time.