THE INSTALLATION

We invite you to engage with Dartmouth's collections in spaces both new and familiar behind our stunning façade. Beyond the front doors is the spacious Russo Atrium, the central axis of the new Hood, which houses a grand welcome desk, as well as comfortable lounge chairs and tables. On the far side of the room is a floor-to-ceiling felt material wall, designed by the architects as a nod to the Hood's wide-ranging collection. It is through this lively atrium space that visitors can access the galleries.

The museum's curators have taken full advantage of the expansion's increased gallery space to present a wider selection of art from around the world and throughout time. In the first-year hang, the new museum will include guest-curated exhibitions of Native American art, African art, contemporary Indigenous Australian art, and the art of Papua New Guinea. Highlights of the Hood's collection of European Old Masters, American art, and antiquities will also be on view. A gallery-by-gallery walkthrough follows here.

KAISH GALLERY

According to John Stomberg, the Virginia Rice Kelsey 1961s Director, the entrance gallery will "set a tone for the whole visit." It surveys contemporary art that engages with issues of feminism and globalism, as well as national, ethnic, and gender identity, and underscores the Hood's dedication to art that expresses social concern.

Stomberg decided to foreground Obiora Udechukwu's Our Journey, a large-scale painting that was created during a time of turmoil in Nigeria. Following the presidential election in 1993, which was annulled by the military dictatorship, the country began a downward spiral from which it has yet to fully recover. "By immediately confronting visitors with a huge, majestic, but likely unfamiliar painting," Stomberg notes, "we reveal a core Hood belief: not all great art is familiar."

The first gallery is intended to inspire a reconsideration of the notion of a "masterpiece" as being well known or popular. "We hope to presage the many amazing 'discoveries' that await in our galleries. A visit to the Hood—as signaled in the first gallery—is not meant to reinforce prior knowledge, but rather to open the door to fresh insights," says Stomberg.

GUTMAN GALLERY

Beyond the entrance gallery is the student-curated A Space for Dialogue installation. Traditionally,

these exhibitions have featured shows curated by individual students and drawn from the museum's permanent collection. However, this opening installation is unique, as it was jointly curated by five 2017–18 Hood senior interns. "We asked our five interns to group curate a show using photographs acquired by Dartmouth students through the Hood's Museum Collecting 101 program. Out of roughly 25 photographs, they chose 12 to include in their exhibition," says Amelia Kahl '01, associate curator of academic programming.

Their show, Consent: Complicating Agency in Photography, asks questions about consent in photography and is organized into four sections: Self-Reflection, Individuals and Identities, Public Spheres, and Global Ethics. Kahl places a spotlight on Mário Macilau's photograph, from his Living on the Edge series, which "explores one visual solution for portraying the issue of poverty in Africa without exploiting his subjects," and Doug Rickard's photograph of the Bronx taken from Google Street View, which "brings up issues of surveillance, technology, and privacy."

As stated in their introductory text, the student curators wanted this exhibition "to start critical conversations . . . [and] reflect the diverse challenges presented by our increasingly globalized world."

KIM GALLERY

Next, visitors step into an installation called Global Cultures: Ancient and Premodern, which houses works created by diverse societies and cultures that date from 1000 BCE to the seventeenth century. "Many ancient galleries in museums favor a narrative, either by placement within the museum, or through their organization, which privileges ancient Mediterranean cultures. We have purposefully worked against that reading through organizing the gallery by themes or object types, such as vessels, figures, or animals, and giving each work its own space," says Katherine Hart, Senior Curator of Collections and Barbara C. and Harvey P. Hood 1918 Curator of Academic Programming. The works on view symbolically reflect the value of learning about diverse societies and cultures through the objects stewarded by academic museums.

Visitors will also notice in this gallery the imposing array of six Assyrian reliefs, which remain at the heart of the museum. "Opposite the reliefs, the bronze sculpture of the ancient Hindu goddess Parvati, associated with fertility, love, and devotion, is accompanied on either side by two Hindu celestial female beings. These face the masculine Apkallu, the sages or genies who protect the Assyrian king against evil spirits," says Hart.

ALBRIGHT GALLERY

At the south end of the first floor of the original museum, an African art installation encompasses various aesthetic values and worldviews spanning the continent. The highlighted themes—Figures, Parliament of Masks, Power Objects, Transitions, Art of Small Things, and Art of Everyday—address common political and cultural histories. Guest curator Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, former curator of African art at the Hood, emphasizes that one goal of this gallery, titled Shifting Lenses: Collecting Africa at Dartmouth, was to "reflect the history of collecting African Art at Dartmouth and the intellectual debates that may have informed or inspired choices."

Nzewi also notes that while there is a tendency to present African art as emblematic and encompassing of daily life in traditional African societies, objects in an art museum should be treated as art. "[T]hey are aesthetic objects. They no longer behave in the ways they were once imagined or serve their original purpose. Instead, they have taken on a new life as museum objects."

While all works on view provide interesting insights into the African cultural experience, Nzewi spotlights the Senufo bird (horn bill) sculpture associated with Poro, an all-male secret society in Cote d'Ivoire; the rare Tusyan female mask called the lonkainen from Burkina Faso; and the Benin waist pendant, a miniature portrait of a court official of the ancient Benin kingdom, which is of inestimable value and is "arguably the most significant object in the Hood's African collection in spite of its small size."

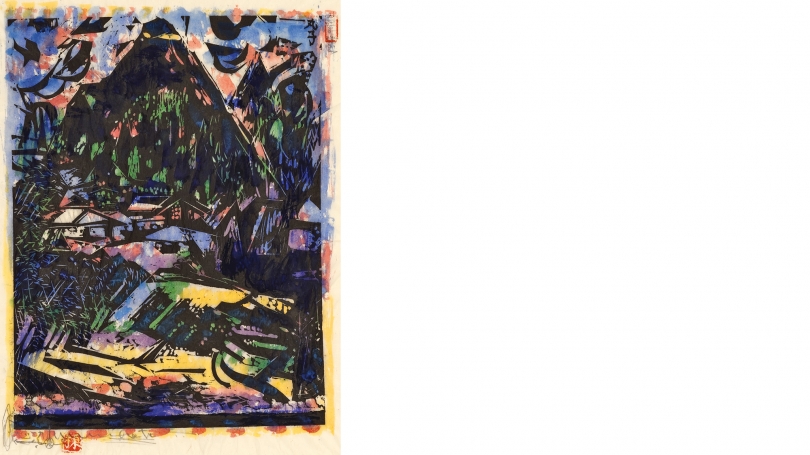

CLASS OF 1967 GALLERY

At the foot of the original Charles Moore staircase lies an intimate installation of works on paper. Unlike the other galleries, the current exhibition in this space focuses on the works of one individual, Japanese artist Munakata Shikō (1903–1975), one of the greatest twentieth- century Japanese calligraphers and woodblock printmakers. The Hood happens to have an exquisite and rare collection of the artist's work, thanks to his special connection with Dartmouth. In 1964–65, Munakata was invited to Dartmouth to participate in a yearlong celebration of Japanese art and culture, and he presented a public lecture and demonstration to formally close a year of weekly programs. He returned shortly thereafter to receive an honorary degree from the College.

"When contemplating how to install the gallery, we thought it fitting to explore the work of an artist who had such an impact on Dartmouth and to highlight how our interactions with art and artists can have a lasting impact on how we see and interpret the world," says Juliette Bianco '94, deputy director of the Hood.

Upon receiving his honorary doctorate, Munakata gifted six works on paper to Dartmouth— including two calligraphies he made for the College in 1965, which are "rare and spectacular examples of the artist's work [that] have never been on view to the public," says Allen Hockley, associate professor of art history at Dartmouth and guest curator for this exhibition. Included in the Munakata show are works by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), a great artist who shaped Munakata's interpretation of the world. A few of Munakata's woodblock prints from 1962–63 depicting the Tōkaidō, the ancient Japanese highway between Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, are paired with examples from Hiroshige's famous Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō print series.

LATHROP GALLERY

At the top of the Charles Moore stairs is our renovated global contemporary gallery, which focuses on Africa for the reopening hang. The featured works comment on the following themes: impacts of the colonial past on nation building in Africa, feminism, urbanism and infrastructural changes, globalization, forced and voluntary immigration, and today's environmental challenges.

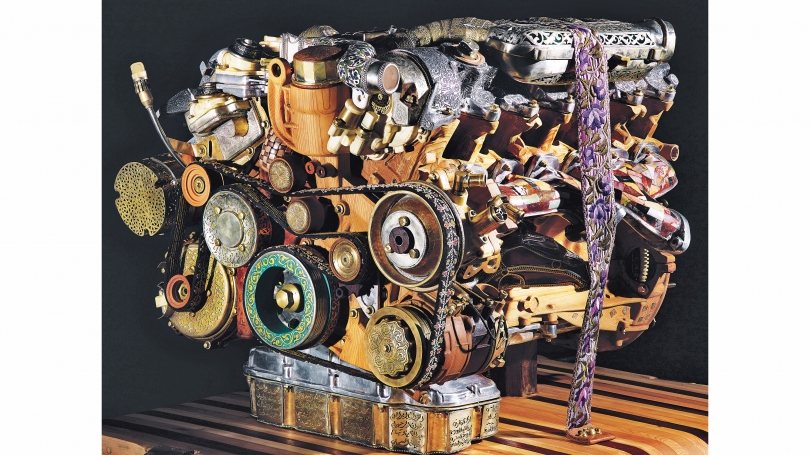

Visitors will see works such as V12 Laraki and V12 Laraki Gearbox by the Belgian, Cameroon-raised artist Eric van Hove. The Laraki project was inspired by the story of Moroccan entrepreneur and designer Abdeslam Laraki, who set out to build a sports car but imported the Mercedes- Benz V12 engine from Germany. V12 Laraki is an exact replica of the Mercedes-Benz engine of the same name but produced in collaboration with about fifty-five Moroccan craftsmen. The exploded V12 Laraki Gearbox was also meticulously handcrafted using different techniques with materials sourced from around Morocco. "The masterly sculpture is a testament to the artist's ingenuity and ability to collaborate with a horde of Moroccan craftsmen," says Smooth Nzewi, who was guest curator for this gallery as well. Nzewi says that while the availability of space constrains the number of works on display, "with the works on view, we are able to offer important snippets of current artistic practices by African artists."

JAFFE GALLERY

The works in this gallery are from the Sepik River and Abelam cultures in Papua New Guinea. Curated by Robert Welsch, associate professor of anthropology at Franklin Pierce University, the exhibition offers a window into the region's traditional religions, people's ideas about the supernatural world, and social relationships within these societies. Katherine Hart says of the viewing experience: "One is able to study works with similar functions side by side—this will be especially evident in the display of canoe prows, drums, suspension hooks, and helmet masks."

The art of Melanesia is a particular strength of the Hood's collection, amassed primarily through a few generous gifts. In 1990, Valerie Franklin gifted twelve hundred works initially acquired by her father, Harry Franklin. Although she had no direct connection to Dartmouth, she thought of the Hood as a possible home for this collection through her close relationship with then-curator Tamara Northern, and her conviction that the artworks would be well cared for and integrated into Dartmouth's educational program.

In 1912, while on sabbatical, Dartmouth professor of biology William Patten visited the Papuan Gulf, collecting art in the field; eventually his son gifted 180 of those works. In addition, from the 1960s through 1980s, collector John A. Friede, Class of 1960, donated a number of works from Papua New Guinea, some given with his mother, Evelyn J. Hall, who was a major benefactor to the arts and the museum at Dartmouth.

HALL GALLERY

This gallery contains twenty-five objects from the Owen and Wagner Collection of Contemporary Indigenous Australian Art. Titled A World of Relations, the exhibition explores a series of relationships between spouses, siblings, parents, and children, as well as those bonded by shared lands or experiences. Family ties run deep in these works. Artist Djambawa Marawili, whose work Dhakandjali is on view, has written that "the Knowledge to create patterns and designs is passed from ancestral beings, through families, and takes time to learn. We don't just do it for ourselves: we are using what our ancestors gave us. . . . Kinship and relationships are always in the patterns and designs."

To highlight the connection between kinship and formal aesthetics, guest curator Henry Skerritt, Mellon Curator of Indigenous Arts of Australia at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia, groups works by husband and wife, parents and daughter, siblings, or individuals who are related by marriage or other forms of kinship.

Place and shared experience are also important in Indigenous Australian art. Skerritt spotlights Elizabeth Nyumi Nungurrayi's Parwalla as exemplary of paintings at Wirrimanu, explaining that the tightly overlapping dots and organic arrangements are intended to evoke the abundance of bush foods in the area. "These paintings draw on knowledge of the land and relate to places known to the artists and members of their family and community," says Katherine Hart.

HARRINGTON GALLERY

The European gallery features several major works. The Perugino altarpiece, a well-known Hood treasure, fills the space and spurs conversation. "It holds several mysteries," says gallery co-curator Amelia Kahl. "We still have not been able to locate its original church and therefore the identity of one of the saints. We do know that the painting was done by several artists."

Another well-known work, Pompeo Batoni's portrait of William Legge, second earl of Dartmouth, is on view. "Not only is his family the source of the College's name, but, as an English gentleman on the grand tour, his image of an educated individual studying abroad is still relevant to Dartmouth students today—although study abroad is now much more diverse in terms of students, locales, and intellectual pursuits," Kahl points out.

HARTEVELDT AND CHEATHAM GALLERIES

Native American art will be on view in two galleries, both curated by Rayna Green, formerly at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The first Native American art gallery contains contemporary art, a deliberate choice as it foregrounds the living traditions and contemporaneity of Native American cultures and society. Titled Portrait of the Artist as an Indian / Portrait of the Indian as an Artist, this gallery features a number of portraits and centers on issues of identity. Its sculptural centerpiece is Jeffrey Gibson's stunning WHAT DO YOU WANT? WHEN DO YOU WANT IT? from 2016. One of the most iconic contemporary works in the collection is Bob Haozous's Apache Pull-Toy, which employs humor and satire to turn the tables on the pervasive "Cowboys and Indians" theme. This overgrown toy made of painted steel is chock full of holes, indicating that the Apache of the title has gotten the better of his cowboy rival.

Another work of note in the contemporary gallery is a large photograph by the performance artist and photographer Rebecca Belmore titled Fringe. The reclining nude female upends tradition by having her back to the camera, lying on a white-sheeted table, with a wound across her back.

The second gallery, titled Native Ecologies: Recycle, Resist, Protect, Sustain, contains both historic and contemporary art. One work that points to the practice of reuse is a pair of upcycled Inunaina (Arapaho) moccasins, made in the twentieth century with reused pieces of painted leather bag for the soles of the feet.

SACK AND RUSH GALLERIES

Two galleries showcase the museum's non- indigenous American holdings in an installation titled American Art, Colonial to Modern. Featuring more than eighty objects in a range of media by artists of diverse personal backgrounds, these galleries highlight some of the social, economic, and aesthetic developments that shaped Euro- American artistic production. Visitors can see the influence of European styles as well the impact of urbanization, immigration, and industrialization in works that mark moments in the United States' evolution as a country.

When discussing the criteria for this reopening selection, Barbara MacAdam, the Jonathan Little Cohen Curator of American Art, cites her aim to include aesthetically strong works that shed light on their historical and cultural contexts. "I especially tried to seek out objects that provide a window into the time and place in which they were made," she says.

The Jolly Washerwoman by Lilly Martin Spencer is such a window, with its references to immigration and the shifting ethnicities of American citizens. Spencer depicts her own servant looking out at the viewer with a toothy grin while scrubbing the family's clothes. "The painting sparks conversations around such diverse topics as class, immigration, servitude, and the use of humor in art," says MacAdam.

Regis François Gignoux's panoramic 1864 canvas New Hampshire and George Inness's 1893 In the Gloaming are just three decades apart, and both reflect a strong veneration for nature. But their "contrasting subjects and aesthetic strategies evoke very different moods and ideas about the natural world." MacAdam concludes that "despite the different time periods in which the works in the gallery were made, they invoke emotions that visitors can relate to today: introspection, sorrow, nostalgia, pride, wonderment. The list could go on."

ENGLES GALLERY

The inaugural sculpture gallery installation is titled Emulating Antiquity: Nineteenth-Century European and American Sculpture. Home to works such as Harriet Hosmer's bust of Medusa and the figure of Icarus by Arthur Gilbert, this gallery places an emphasis on the figural. Katherine Hart talks about Hosmer's Medusa by saying that this portrayal of the snake-headed figure was unprecedented: "She depicts Medusa as Ovid describes her—as being both beautiful and terrifying."

"The art in the sculpture gallery is academic in character," says Hart, "and not so long ago, these artists were often ignored by art historians due to their work being classified as decorative and conservative in a time when avant-garde painters were popular."

However, over the last thirty years, the lenses through which we view this art have shifted, prompting the exploration of themes such as homoeroticism, sexuality, and changing aesthetic ideals. "Scholars who are interested in questions of gender and society and the politics of public sculpture are now taking a closer look at these artists and their work."

Jutting out from this gallery is a unique vitrine, visible from Dartmouth's green, which will house a variety of works on a rotating basis.

CITRIN GALLERY

The gallery next door, featuring a transatlantic modern art installation titled Cubism and Its Aftershocks, contains works that embody the major artistic innovation of the early twentieth century, a change spurred by the exchange of ideas between international art centers. Visitors will see Pablo Picasso's Guitar on a Table, a work that encapsulates an important moment in the development of Cubism, a groundbreaking aesthetic that established new ideas of abstraction.

"Picasso ignited the imagination of countless artists, and his development of Cubism, along with Georges Braque, was particularly influential," says John Stomberg. "We find echoes of his ideas in nearly every work of art in this gallery."

Stomberg explains that this gallery "focuses on the sharing made possible by 'rapid' ship travel between France and the United States" and looks particularly at Parisians and New Yorkers in dialogue. "A great example of [transatlantic] transmission can be seen in comparing the Picasso with the Preston Dickinson. Clearly aware of his European colleague's new approach, Dickinson nonetheless 'Americanizes' Cubism with his choice of subject matter—casting aside the classicism of the guitar and the café for machine-age icons such as factories and cities."

NORTHEAST GALLERY

While the transatlantic modern art gallery follows mostly a two-way exchange, the postwar gallery hints at the growing globalization that begins after World War II with vital centers developing in places like California, Washington, DC, and Japan. The gallery space, with its high ceiling and singular east-facing window, "embodies drama, [and the] art here has to be individually and collectively powerful to stand on its own in such a space," says Stomberg. "Each work in this gallery is forceful, stunning, moving, and bold."

The postwar gallery is home to several incredible works of art. Japanese artists Atsuka Tanaka, Hisao Domoto, and Yayoi Kusama were leading lights in the period while offering different approaches to form and content. Stomberg relishes the opportunity to display these works: "It strikes me as a luxurious moment to get even a little depth in this period of Japanese art."

We hope you will return to the installations often and share your impressions of the new Hood with us, and on social media, as we realize our vision of a teaching museum in the twenty-first century.

Isadora Italia

Campus Engagement Coordinator

Andre Scherding

Summer Museum Intern, 2018