By now, you may know that the newly renovated and expanded Hood Museum of Art will open to the public on January 26, 2019, following more than two years of construction. With the expanded museum, our 65,000+ works will be better preserved, seen, and utilized by students, faculty, and all visitors. By restoring and updating the original 1985 building and adding new facilities, we'll increase our capacity for teaching, exhibitions, and dialogue. This new design will also create a central artery through the campus arts district facing the Dartmouth Green.

We must admit, we’re incredibly excited!

As we gear up for the Hood’s reopening, we can’t help but look back and reflect on the history and journey of Dartmouth’s collection. Before the building was constructed, where did all those objects live? Why and how did Dartmouth start collecting? Has teaching with objects always been a priority for the College?

The collections of art and artifacts at Dartmouth can be traced back to the College’s founding in 1769. At the school’s second commencement in 1772, Dr. John Phillips gave the young institution £175 with which to acquire a “philosophical apparatus” (a standard set of scientific equipment). That same year, Reverend David McClure, a tutor at Dartmouth, wrote to President Eleazar Wheelock that he had acquired “a few curious Elephants Bones” for the school.1 In 1773 the College received its first fine art piece: a silver monteith from John Wentworth, royal governor of New Hampshire and a Dartmouth trustee.

While these three objects seem an eclectic beginning for what is now known as a museum of art and material culture, we must think back to the concept of a museum in the eighteenth century (which has a surprising resonance with the Hood today). During that time, such collections were generally referred to as cabinets of curiosities, which could consist of anything from fossils to antiques to ethnographic artifacts. Furthermore, Dartmouth's traditional role as a college in rural New England inspired a commitment to providing students with examples of the "natural and moral world" beyond their immediate surroundings, giving birth to a collection of objects capable of teaching lessons about science, nature, and cultural history.

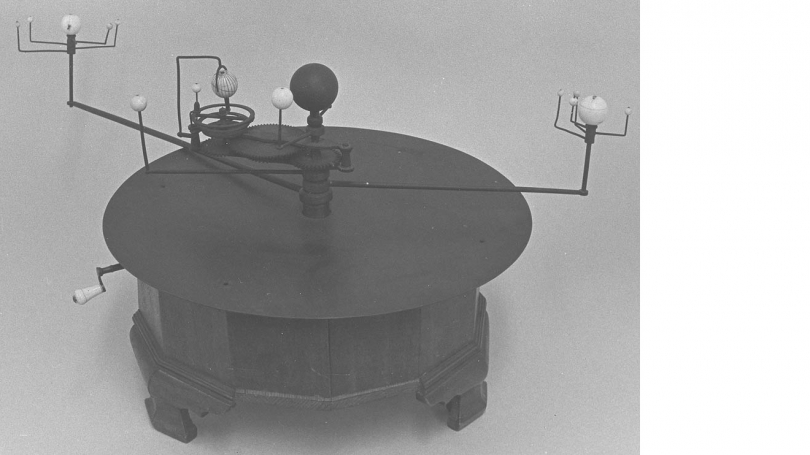

Examples of collecting for the benefit of curricular teaching into the nineteenth century include “coins and curiosities” obtained by second Dartmouth President John Wheelock on his tour of France, Holland, and Great Britain; an orrery (see below), or cosmoscope, a mechanical device that illustrated the movements of the solar system; Native American art and material culture; Assyrian reliefs from the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II (883—859 BCE); and European paintings.

Throughout this early period, the College’s art and artifacts were housed in a variety of locations. Until 1811 they coexisted on the third floor of Dartmouth Hall, separating two student residence areas. (Though the inclination to house the collection near the students was noble, it caused residents a logistical inconvenience, to the point that some young neighbors blew down the walls of this “museum” with a cannon).

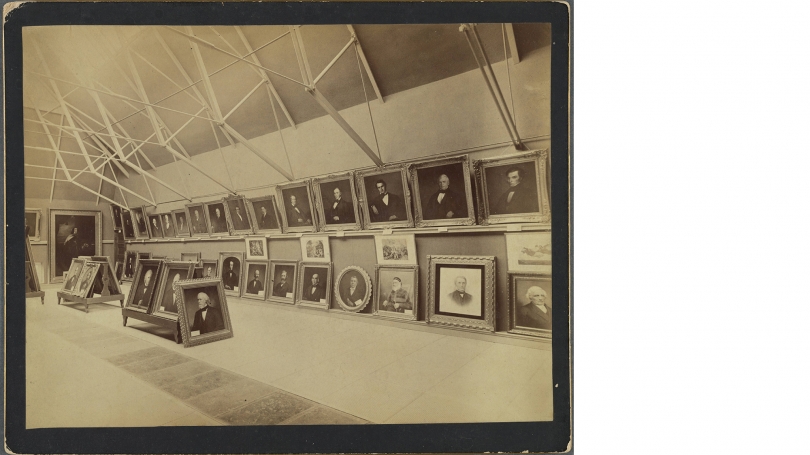

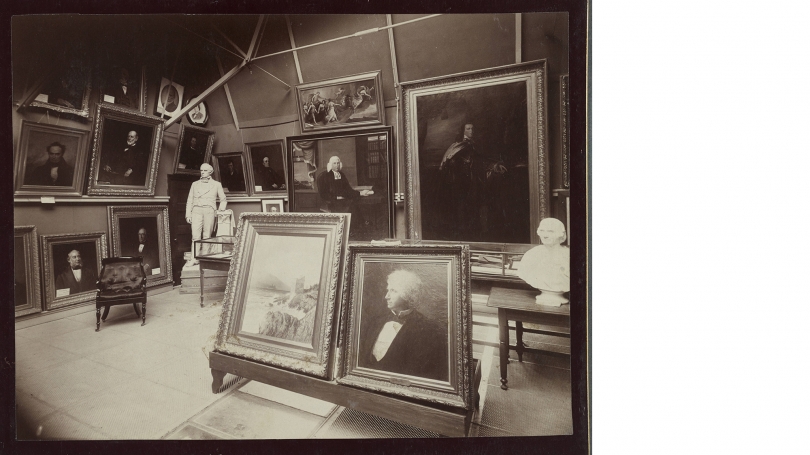

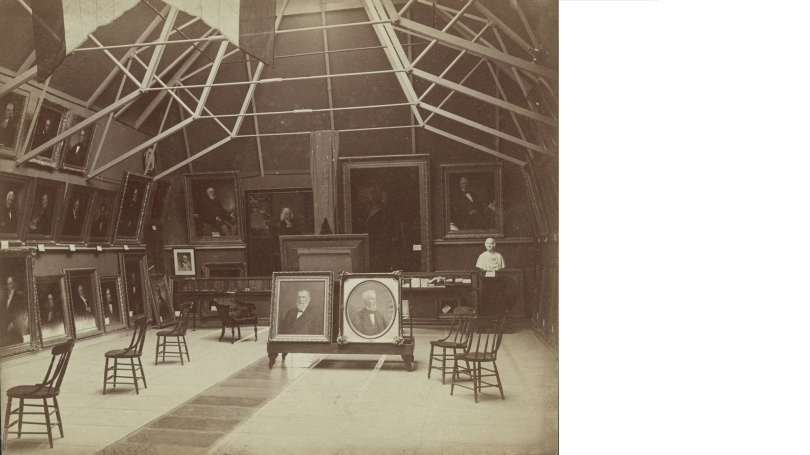

By the late 1820s, Thornton Hall became the new home to the Dartmouth College Library and Dartmouth Gallery of Paintings, while the Dartmouth College Museum collection, composed of scientific, ethnographic, archaeological, and natural history objects, remained in Dartmouth Hall. The two sections of the collection would remain separated until 1840, when Reed Hall was completed, and they were reunited again for thirty years.

The objects then began a series of separate migrations. The museum collections moved to Culver Hall (since demolished) in 1871, and the Library and Gallery of Paintings went to Wilson Hall when it opened in 1885, complete with a gallery on its top floor. In 1895 the museum collections were once again moved, to Butterfield Hall, which housed the Butterfield Museum of Paleontology, Archaeology, Ethnology, and Kindred Sciences thanks to a donation by Ralph W. Butterfield, Class of 1839. In 1928 Butterfield Hall was demolished to make room for Baker Library, and the bulk of the museum collection went to Wilson Hall.

Despite over a century of collecting objects, the College offered no courses to foster the interpretation of art until 1905, when it introduced courses on Renaissance and Baroque art history, following a growing trend among American institutions. Around this time, Henry L. Moore, Class of 1877 and longtime trustee, made a large gift in honor of his late son that would allow the College “to purchase objects of artistic merit and value . . . [t]o encourage and promote the interest and education in art of the students.”2 This donation marked Dartmouth’s first acquisitions endowment and led to a significant expansion of the College’s holdings.

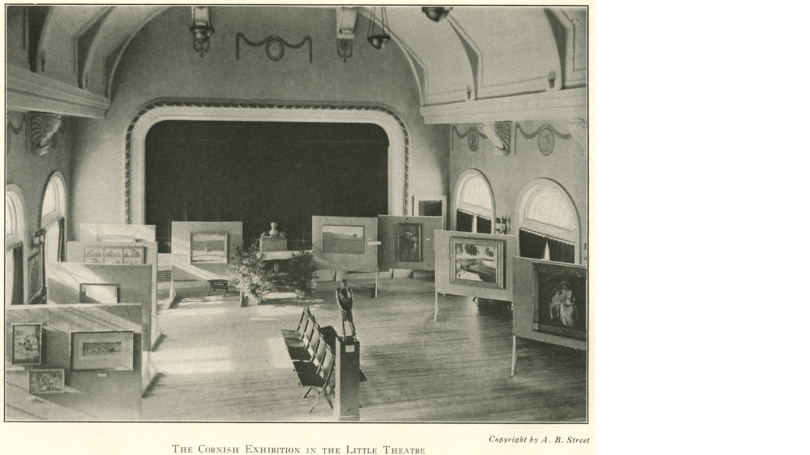

As the collection grew, so did direct engagement with artwork. George B. Zug (1867– 1943), art history professor at Dartmouth from 1913 to 1932, was an early and enthusiastic proponent of this cause. He and his students coordinated interdisciplinary installations of original artworks in the Little Theater of Robinson Hall. Students assisted in selecting objects, arranging loans, writing labels, producing posters, and giving public talks.

In 1927 prosperous manufacturer and banker Frank P. Carpenter (1846–1938) gave then– Dartmouth President Ernest Martin Hopkins funds to erect a building specifically for the Art Department. Carpenter Hall opened in 1929 with the promise of consolidating fine arts holdings, classrooms, offices, and an art library in one building. For the first time, the “under one roof” concept came to campus.

Over the next three decades, the collection grew and grew, primarily under the purview of Churchill “Jerry” Lathrop, who arrived at Dartmouth in 1928 and remained until 1969 as a professor and director of the art galleries, a position he accepted in 1934. Lathrop founded Dartmouth’s Sherman Art Library and artist-in- residence program, and drove numerous donations and acquisitions.

Eventually, Carpenter Hall’s galleries and art storage areas could no longer accommodate the collection. Cramped conditions, coupled with a rising need for a performing arts center, resulted in construction of the Hopkins Center, where President John Sloan Dickey envisioned all creative arts brought together.

When it opened in 1962, “the Hop” provided two additional galleries for exhibitions and displays, purposely placed near the student mailboxes and snack bar to embed them into the mainstream of campus life.

While this added visibility and integration was positive in many regards, it also had dramatic consequences. The administration of the galleries was incorporated into the Hop, and special exhibitions were housed there, but the art history faculty, art library, and permanent exhibitions remained across campus at Carpenter Hall. This created a precarious situation, as fragile works had to be transported back and forth and put at risk of wear and weather.

In 1974 the art and anthropology collections were brought together into one administrative unit under the combined name of the Dartmouth College Museum and Galleries, and the College decided to divest itself of its natural history collection. Fortunately, Dr. Robert Chaffee, then-director of the Dartmouth College Museum, was allowed to use the natural history collection to found a regional museum in the Hanover area—the now-thriving Montshire Museum of Science—which places an emphasis on learning science with objects as well as through interactive discovery.

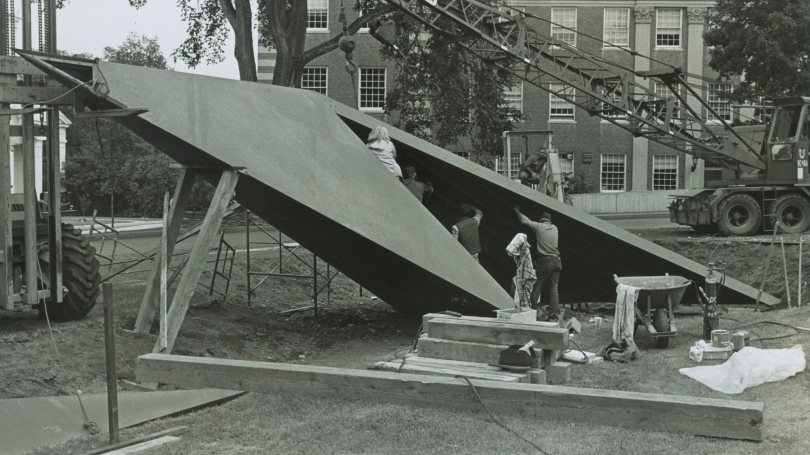

Another interesting development that occurred around the 1970s would expand the collection in a new direction. In the fall of 1974, Jan van der Marck arrived on campus as director of galleries and brought a passion for contemporary art and a bold exhibitions and acquisitions program. His belief that students should be confronted with the art of their time in their everyday lives led to several contemporary outdoor sculptures being installed around campus.

Though this was an impressive period of growth, Dartmouth remained an institution with a collection but without a proper museum.

In 1976 then-Director of the Hopkins Center Peter Smith outlined the need for an independent art museum, stating that Dartmouth would only be able to adequately teach its students connoisseurship with a new center devoted to the exhibition and contemplation of works of art. In addition, a new museum would become a great regional center, affecting a community much broader than just the College, and therefore attracting new gifts of art. Funding to meet this goal was assured in 1978 when the College received a large bequest from Harvey P. Hood (1897–1978), Class of 1918 and a trustee from 1941 to 1967.

On September 28, 1985, the Hood Museum of Art opened to the public. Designed by Charles W. Moore of Centerbrook Architects, the 40,000- square-foot postmodern building included ten galleries, a study-storage facility, and administrative spaces, as well as a 204-seat auditorium. At that time, the collection contained more than 40,000 pieces, and the consolidation of galleries, offices, storage facilities, and teaching spaces into one independent building finally provided the opportunity to appropriately serve the museum’s audience of students, scholars, and the general public.

Fast forward a few years, and we’re ready for our next chapter to begin with the reopening of the new Hood Museum of Art on January 26. We can’t wait to see you there!