Photography at the Hood: An Update

The two biggest stories of twentieth-century art were abstraction and the emergence of photography. The first is well represented in all its variety by the Hood collection, from its 1912 Pablo Picasso to the Mark Rothko, the Ellsworth Kelly, the Alma Thomas, and the Pat Steir, among many other great works of art. The second story is one we are now redoubling our efforts to tell fully. There are many issues with developing a photography collection, and first among them is the many histories with which the medium is involved. Art is but one trajectory worthy of attention. We need to consider documentary (which has always had an uneasy, yet fruitful, relationship to the ideals of creative photography), photojournalism, scientific photography, crime photography, vernacular photography, portrait photography, survey photography, and many more.

There are also a wide variety of media that fall under the rubric. Almost every photographic approach ever invented is still in play today. Since Daguerre first introduced his complex process for holding an image on a copper plate, enterprising photographers have been using, and improving, the technique. Today, artists from Chuck Close to Binh Danh are actively engaged with updated approaches to daguerreotype. And there are artists making tintypes, ambrotypes, cyanotypes, and Van Dyke Brown prints using pinhole cameras and the plastic-lensed Diana or, at the other end of the spectrum, view cameras that create huge negatives or the new Hasselblad H6D that creates 100-megapixel captures. Photography today is seemingly endless.

Our charge has been to decide how to focus the Hood's collection; we cannot cover all of the stories of photography. But, in the context of Dartmouth and its longstanding association with issues of social concern, from the environment to international understanding, a promising shape for the collection has emerged: photography and society. This umbrella is broad enough to allow flexibility while also offering a sense of direction. We are looking at images that reveal or address both the impact of environment and events on people and, importantly, the reverse. Great photographs offer insight into complex issues without reducing them to simple tropes. The specific goals of the person who released the shutter may vary widely, as may the resultant images, but the photographs we are after offer rich rewards to those who study them carefully.

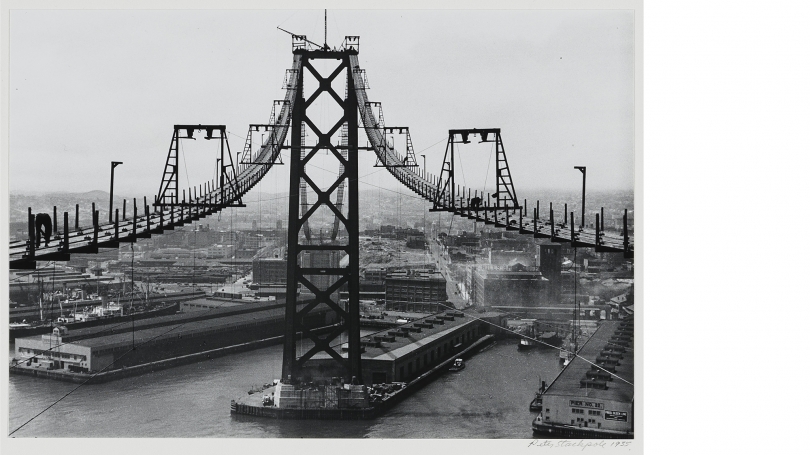

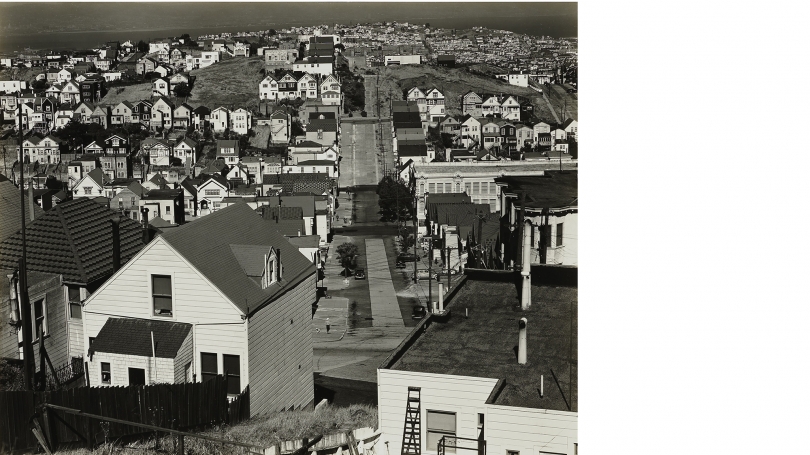

The Hood will continue its established focus on creative photography and master prints (indeed, we recently acquired thirty vintage and lifetime Brett Weston prints, but the collection will expand to include work that tends toward the documentary and/or photojournalistic). As announced last fall, the James Nachtwey archive will form a new anchor for an expanding collection. More recently, we moved to acquire twenty-seven vintage prints by a pioneer of picture magazine photography, Peter Stackpole, whose long career as a photojournalist was primarily in the service of Life magazine. His work took him far afield, particularly when he covered the Pacific Theater during World War II. He is best remembered, however, for having chronicled his native California—from the Bay Area's soaring bridges under construction to Hollywood directors, stars, and wannabes. He typically used a small 35mm camera that facilitated access to challenging shooting sites and accentuated the dynamic, frank quality of his work. Many of his studied bridge construction shots from the 1930s, taken from odd angles and accentuating the structures' underlying geometry, have a modernist quality. In contrast, the candid feel of his later Hollywood photographs—even when posed—gives them an air of familiarity that appealed to fans hungry for "up close and personal" views of movie stars.

In 1936, when Time, Inc., hired Stackpole, he joined Margaret Bourke-White, Alfred Eisenstadt, and Tom McAvoy as a staff photographer for the then-new Life magazine. During his twenty-five-year career with Life, Stackpole earned acclaim for his wartime photographs and, especially, his behind-the-scenes images of Hollywood directors and glamorous stars on the set, at home, and out on the town. Over time, Life published twenty-six of his photographs as cover illustrations. After leaving Life in 1961, he moved back to San Francisco and taught photography at the Academy of Arts College. Disaster struck in 1991, when a wildfire swept through his Oakland home, destroying most of his negatives. Fortunately, Life maintained an archive of his images, others were in the safekeeping of the Oakland Art Museum for an exhibition, and still others were with his dealer at the time.The Hood Museum of Art's collection of Stackpole photographs comes from the latter collection, which was later acquired by the artist's family.

It is hard to comprehend today how important Life photographs were in shaping public perception before the advent of television news. First, millions of copies were sold each week and they had a "pass around" rate (think of a dentist's office, for example) that exceeded all of their competition. In other words, a significant percentage of the American population relied on the magazine for their images of world events, and to study these images is to study visual rhetoric and its impact on social and political history. Few images today achieve the singularity of Life photographs, because even contemporary press photographs are but part of an onslaught of complementary images that we receive via websites and social media. During its peak in World War II, Life provided a shared visual experience in the United States on a scale that may never be repeated. Having the original prints of one of their signature photographers allows us a glimpse into not only the subjects themselves but also the awesome power of the photograph in society.