This exhibition of thirty etchings from the Hood Museum of Art's collection represents a nearly complete set of Venice-inspired prints by Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697–1768), known as Canaletto. These etchings were ultimately donated to the museum by Jean K. Weil, following the wish of her late husband, Adolph "Bucks" Weil Jr., Dartmouth Class of 1935. Mr. Weil was an astute and prescient collector of Old Master prints and an extraordinarily generous patron of the museum who also gave to the Hood exceptional prints by such artists as Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, Rembrandt van Rijn, Jacques Callot, and Francisco Goya. Through this exhibition devoted to Canaletto, the Hood is honored to highlight an important facet of Mr. Weil's distinguished collection in recognition of the one hundredth anniversary of his birth.

It is difficult to imagine an artist more intimately associated with a city than Canaletto. For centuries, his name has been synonymous with topographical cityscapes of Venice known as vedute (views). His luminous, meticulously detailed paintings of such familiar vistas as the Grand Canal and Piazza S. Marco celebrate the city's stunning beauty and became coveted mementoes for English gentlemen to bring home from the Grand Tour. Given his fame as a landscape painter and the demand for his trademark Venetian scenes, it is remarkable that he turned, albeit very briefly, to a new medium and format for his art. In the early 1740s, Canaletto embarked on a project to create a series of etchings dedicated to (and most likely financed by) Joseph Smith, the British consul to the Venetian Republic, who acted as his agent on behalf of foreign collectors. Unlike his painted views of Venice, the vedute prints present an unexpected side of the artist and offer an alternate window into eighteenth-century Venetian life. The scenes are intimate and creative, often pastiches of real places and imaginary views. With few exceptions, they are not of the expected landmarks but show the more humble, everyday aspects of the city, such as modest dwellings and little byways; others are fantasies, ranging from elaborate caprices to intimate backyard scenes and wild landscapes. The vedute prints thus reveal an unknown artist and a hidden city and its environs, beyond the vision packaged for tourists and outsiders.

The elaborate frontispiece for the vedute, which dedicates the prints to Smith, is a testament to the close relationship between artist and patron. It also provides insight into the scope of Canaletto's project, describing the works as "Views, some taken from nature, some invented." The imaginative composition of the dedication also introduces the vedute as a departure from Canaletto's previous work. The artist etched the words on what appears to be a tombstone or a memorial, creeping with vines and vegetation. Beyond a wall, the monument is framed on either side by architectural structures that seem typically Venetian in character but cannot be identified. In the foreground, figures marvel at the inscription, and an architectural fragment occupies the right corner. This page brilliantly announces the themes that we encounter in the suite of prints—creative combinations of fantasy and reality, inventive conflations of the romantic past with a precarious present, and a peek at unknown sides of Venice.

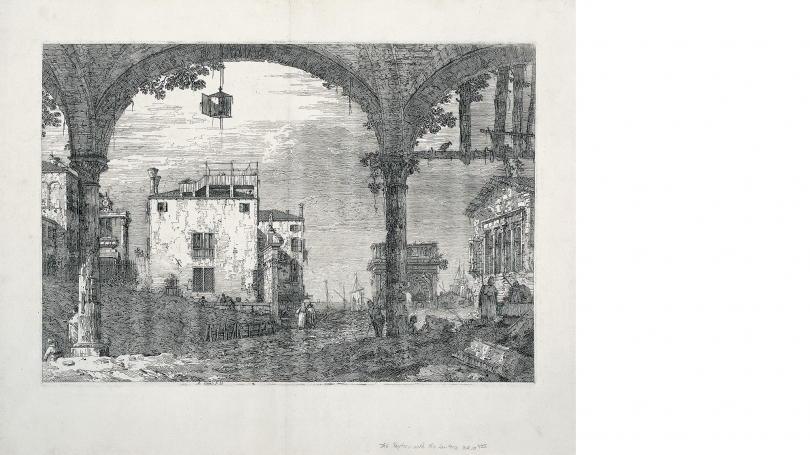

If any print summarizes Canaletto's creative imagination in the vedute, it might be The Portico with the Lantern. The composition is separated into two distinct planes by a portico, which provides cool shade in the foreground as a brilliant sun illuminates the structures beyond. The center arch frames a large yet unassuming house, which includes a timber roof terrace used for drying laundry—a characteristic feature of Venetian vernacular architecture. The house is balanced by a classical temple and triumphal arch on the right. The portico through which we view this scene appears aged and overgrown with vines, littered with architectural ruins of the past. Canaletto, after years of precisely transcribing the glory of Venetian tourist sites, clearly delighted in the creative freedom of this project, combining disparate elements to create a romantic portrait of the Venice he knew so well.

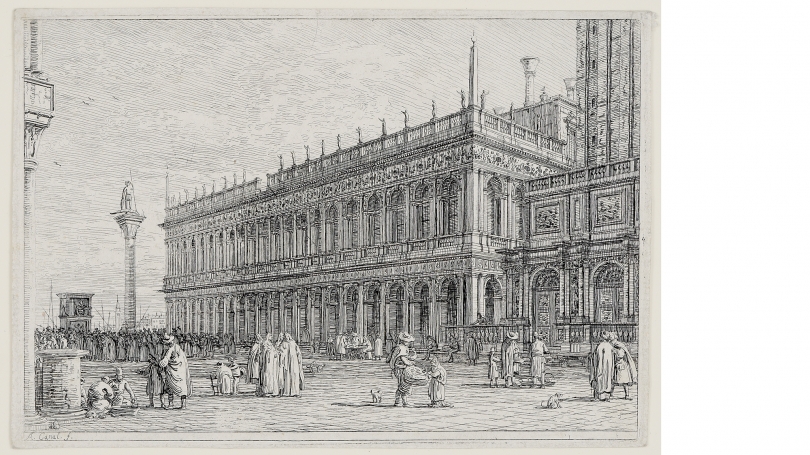

A contrasting approach is evident in the few recognizable Venetian scenes that Canaletto included in the series. In La Libreria, for example, Canaletto gives a familiar glimpse of Saint Mark's Square and the library's façade by architect Jacopo Sansovino, surmounted by statues and obelisks. Although the scene is familiar, Canaletto truncated the view, downplaying the soaring architecture and giving more attention to the activities of everyday Venetian life in the square, such as children playing, nuns promenading, merchants haggling in the foreground, and figures crowded around a puppet theater near the column in the background.

The reason for Canaletto's shift to printmaking at the peak of his fame as a landscape painter remains unclear. A possible factor was that the War of Austrian Succession (1740–48) made travel to Italy difficult for his English patrons, and prints were easier to transport to them than large paintings. Prints could also potentially represent a new source of revenue at a time when Canaletto and Smith saw a drop in the number of visits to Venice by English patrons. Finally, the vedute prints may have been an answer to the artist's critics and detractors, who favored a more imaginative, rather than topographical, approach. For all of their inventiveness and skillful yet spontaneous execution, they are now considered some of the finest examples of etching from the eighteenth century.

This article is adapted from an essay by Sarah G. Powers in the exhibition's accompanying brochure, which was co-published with the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, located in Mr. Weil's hometown of Montgomery, Alabama. The MMFA also benefited from donations from his outstanding collection of prints, including several impressions of Canaletto's Vedute etchings.