Valentine Green (printmaker), after Joseph Wright of Derby (painter); John Boydell (publisher), Experiment on the Air Pump, 1769, mezzotint, state ii/IV (scratch letter proof). Purchased through gifts from the Lathrop Fellows; 2008.10.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

INTRODUCTION

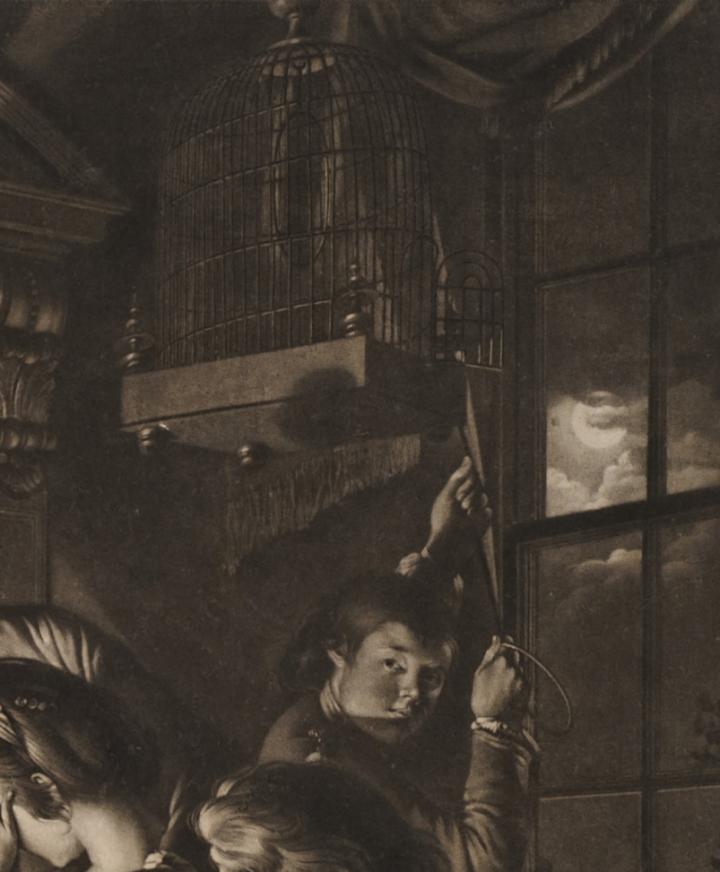

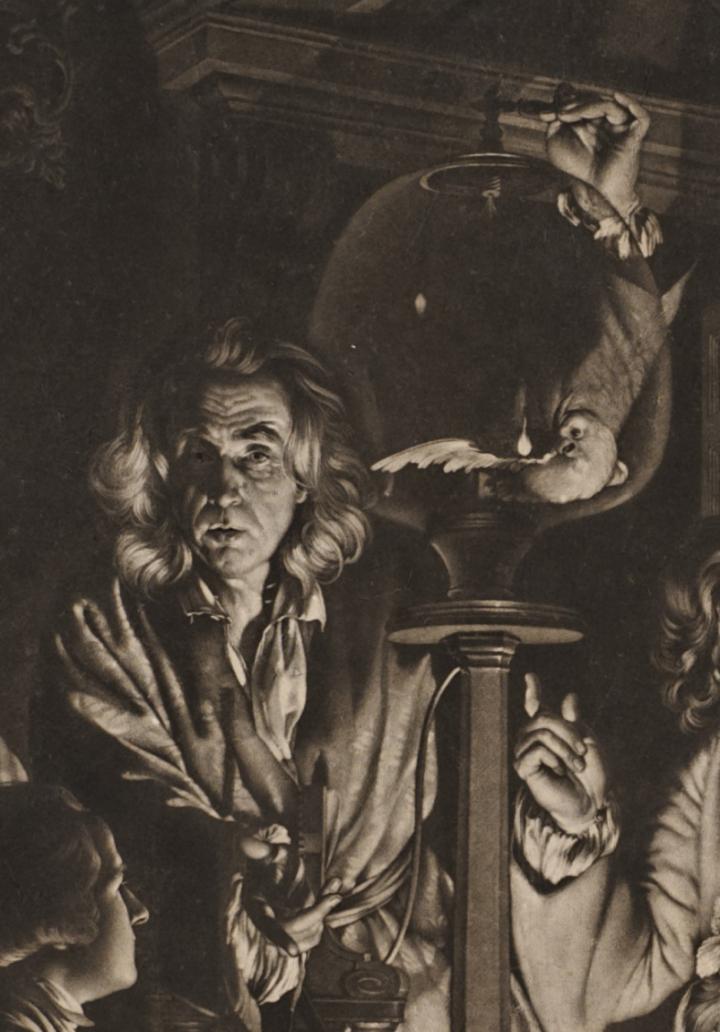

This image was created by Valentine Green, an English printmaker, in 1769. Green was hired by the publisher John Boydell to reproduce a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby entitled Experiment on the Air Pump. In this scene, a family has gathered around to test an air pump and explore the newly discovered role of oxygen to support life. If the pump works correctly, all of the air will be sucked out of a glass chamber into which a bird has been placed, and the bird will die. The image reflects and comments upon the active interest in science in the eighteenth century.

Green used a relatively new printmaking process known as mezzotint for this work. Mezzotints were uniquely capable of capturing, in black and white, the textures and qualities of oil painting. Prints were produced by publisher and made available at an affordable price so that many people were able to see and own the images.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see.

Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you see or notice when you look at this scene?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work with questions like these:

* What do you notice about the light? What does it illuminate? What is cast into shadow?

* What do you notice in the background? Outside the window?

* Examine each group of figures. Describe their dress, pose, and facial expressions. How is each person responding to the experiment?

* What is the role of this man?

* Mezzotints capture textures beautifully. Name some of the different textures shown in this work.

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work.

For instance:

* Where does this experiment seem to be taking place? How does the lighting affect the mood of the scene?

* Why do you think each of these figures was included in the painting? What is the role of each? Do they have a relationship to one another?

* What do you think will happen next?

After each response, always ask, "How do you know?" or "How can you tell?" so that students will look to the work for visual evidence to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

At the end of this document, you will find some background information on this object. Read it or paraphrase it for your students.

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* What does this image tell us about how ordinary people experienced science in the eighteenth century?

* What is the artist challenging us to think about the "new age of science" based on this image?

* This image was very popular and sold very well. Why do you think that was the case?

* How do you think the availability of mezzotints changed the art market in England in the eighteenth century?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Do you think this print is successful and well done? Why or why not?

This fifth stage can also encompass one’s response to a work of art. One’s response can be much more personal and subjective than one’s assessment.

* Do you like this work of art? Does it move you?

* Do the ethical issues raised in this image still resonate today? How so?

Background Information

Valentine Green, English, 1739–1813 (printmaker), after Joseph Wright of Derby, English, 1734–1797 (painter); John Boydell, English, 1719–1804 (publisher)

Experiment on the Air Pump

1769

Mezzotint, state ii/IV (scratch letter proof)

Purchased through gifts from the Lathrop Fellows; 2008.10

Before the advent of lithographic and photomechanical reproductions, mezzotints were the favored medium for publicizing English paintings. First invented by a German printmaker in the mid-seventeenth century, the mezzotint—from the Italian mezzo ("half") and tinta ("tone")—was a tonal method better able to represent the painterly qualities of light and shadow than traditional printmaking techniques, such as engraving and etching.

Although generations of painters had used prints to promote their compositions, the establishment of regular public exhibitions in London in the second half of the eighteenth century significantly increased popular demand for inexpensive and widely available editions of fashionable pictures. Artists and collectors were especially attracted to the dramatic appearance of mezzotints.

The painter Joseph Wright of Derby used printmaking aggressively as a way to promote his work. Fourteen of the paintings that he exhibited in London between 1765 and 1772 were printed—twelve of them as mezzotints. The prints served as a lasting record of the artist's most notable examples of his early "candlelight pictures," which were characterized by spectacular effects of natural and artificial light. Most of these works were large, multi-figure interior scenes, generally produced on speculation for sale to the general public. In many instances the prints were issued within six months after the paintings had been exhibited, and they were often praised by critics as well.

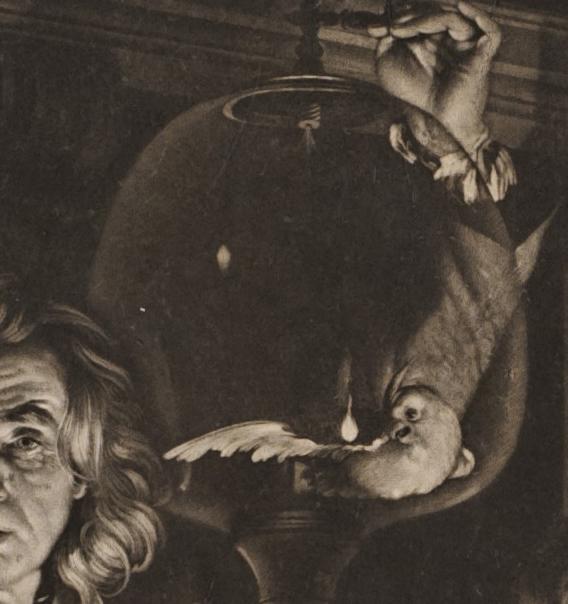

Several of the earliest mezzotint versions of Wright's works were themselves exhibited, including Valentine Green's Experiment on the Air Pump, self-published in 1769 as the printmaker's grandest and most complex print to date. Green faithfully rendered the depiction of a variety of poses and facial expressions, heightening the nighttime drama of a family observing a traveling lecturer as he demonstrates the potentially lethal effects of creating a vacuum in an air pump. The image's quality, delicacy, and precision soon attracted the attention of the publisher John Boydell, who purchased the plate immediately after the exhibition of Green's mezzotint and reissued it in late June of the same year.

In this scene, a family has gathered to witness and learn about various experiments in pneumatic physics, the scientific study of air and other gases. This test involving a bird had become commonplace by this time. The air pump was invented in Germany in 1650; by the mid-eighteenth century, it was a standard device in science lectures. (The first three technical apparatuses that Dartmouth College obtained in the late eighteenth century were an orrery for tracking the movement of the planets, a telescope, and an air pump.) The image highlights the active interest in science in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Experiment on the Air Pump is perhaps Wright's greatest achievement, a large and complex narrative that addresses the contemporary interest in science while subtly raising issues of ethics and morality. Recent interpretations—noting the "curious human skull" in the glass jar on the table—suggest that the picture has a vanitas theme, a reminder that "death is inevitable and its moment unpredictable." Although the composition appears to represent the advance of scientific knowledge, the subject is somewhat gruesome. The experiment is depicted at its most crucial moment: the bird, deprived of air, has fallen to the bottom of the glass globe, and the lecturer can either open the stopcock in time to save the bird or else keep it shut, which would lead to its death.