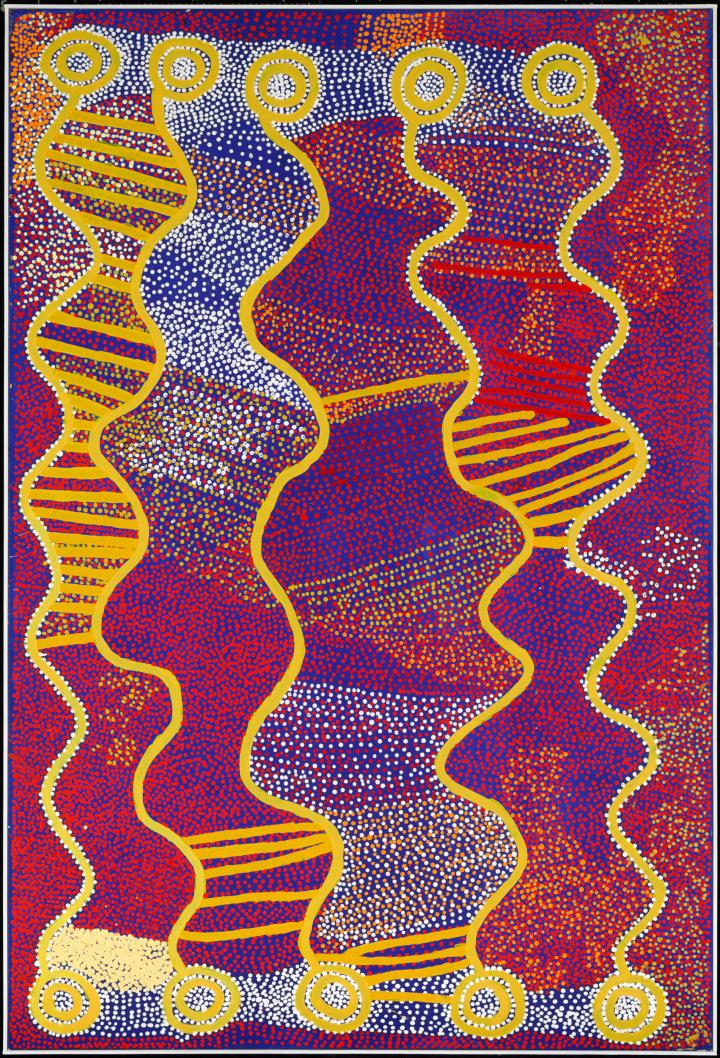

Shorty Jangala Robertson, Ngapa Jukurrpa – Puyurru (Water Dreaming at Puyurru), 2007, acrylic on canvas. Promised Gift of Will Owen and Harvey Wagner; EL.2011.60.45.

Based on the Learning to Look method created by the Hood Museum of Art. This discussion-based approach will introduce you and your students to the five steps involved in exploring a work of art: careful observation, analysis, research, interpretation, and critique.

HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE

1. Print out this document for yourself.

2. Read through it carefully as you look at the image of the work of art.

3. When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom.

4. Use the questions provided below to lead the discussion.

Step 1. Close Observation

Ask students to look carefully and describe everything they see. Start with broad, open-ended questions like:

* What do you see or notice when you look at this image?

* What else do you see?

Become more and more specific as you guide your students’ eyes around the work with questions such as:

* What do you notice about the lines?

- their movement?

- their color?

* What do you notice about the shapes at the ends of the long wavy lines?

* What do you notice about the dots that fill the spaces in between the shapes and lines?

* Their density in different parts of the painting?

* Their movement? their colors?

* What do you notice about the background? Its color?

* The way the background color interacts with the lines and dots on the surface of the painting?

Step 2. Preliminary Analysis

Once you have listed everything you can see about the object, begin asking simple analytic questions that will deepen your students' understanding of the work. For instance:

* Do the lines, shapes and colors of this painting remind you of anything? Perhaps elements in the natural world?

* What effect do the dots have on the eye? How would the painting be different if the dots were blended into fields of color?

* What tools might the artist have used to paint this image?

* Does this painting have depth? Or does it feel like a flat surface?

* How does this painting make you feel? Do you think it suggests something concrete or something more poetic or spiritual?

After each response, always ask, "How do you know?" or "How can you tell?" so that students will look to the work of art for visual evidence to support their theories.

Step 3. Research

Now that your students have had a chance to look carefully and begin forming their own ideas about this work of art, feel free to share with them the background information at the end of this document. It provides information you cannot get simply by looking at this painting.

When you have finished sharing the information, consider the following:

* Does this information reinforce what you observed and deduced on your own?

* Did it mention anything you did not see or think about previously? If so, what?

* How would your experience of this painting have been different if you read the background information first?

Step 4. Interpretation

Interpretation involves bringing your close observation, preliminary analyses, and any additional information you have gathered about an art object together to try to understand what a work of art means. There are often no absolute right or wrong answers when interpreting a work of art. There are simply more thoughtful and better informed ones. Challenging your students to defend their interpretations based upon their visual analysis and their research is most important.

Shorty Jungala Robertson created a painting that not only describes a particular place (the Tanami desert and the water courses above and below ground), but also refers to an ancient story (the Ancestors singing down the rain in a great thunderstorm), and expresses his spiritual connection to the land and its importance to his culture.

Some basic interpretation questions for this object might be:

* What choices did the artist make in order to achieve all this? For instance,

- In what way does this painting suggest a desert? The desert after the rain?

- In what way does the painting suggest water? Rain? River beds or underground springs?

- What signs and symbols suggest the spiritual presence of the Ancestors?

- What about the painting suggests a love for this place or even a spiritual feeling toward it?

* What does this work tell us about the role of art in Aboriginal Australian culture? How is that the same or different from the role of art in American culture?

Step 5. Critical Assessment and Response

Critical assessment and response involves a judgment about the success of a work of art. This step optional but should always follow the first four steps of the Learning to Look method. Art critics often engage in this further analysis and support their opinions based on careful study of and research about the work of art.

Critical assessment involves questions of value. For instance:

* Do you think this painting is successful and well done? Why or why not?

This fifth stage can also encompass one’s response to a work of art.One’s response can be much more personal and subjective than one’s assessment.

* Do you like this work of art? Does it move you?

* Does knowing something about Australian Aboriginal art and culture affect how you perceive or feel about this work?

Background Information

Shorty Jangala Robertson, Warlpiri, born about, 1935, Yuendumu, Western Desert, Northern Territory

Ngapa Jukurrpa – Puyurru (Water Dreaming at Puyurru), 2007

Acrylic on canvas

Promised Gift of Will Owen and Harvey Wagner; EL.2011.60.45

Aboriginal Australian painting is often inspired by a particular place, but it also represents through a sophisticated visual language ancient stories about the ancestors who visited and shaped that place, information about how to care for and maintain the wellbeing of that particular region, and finally the powerful emotional, spiritual, and physical connection the artist and his or her people feel for that location.

This painting depicts a site known as Puyurru in the Tanami Desert. Located in the Northern Territory, the Tanami is the northernmost desert in Australia and is the third largest, covering an area of 71,235 square miles. It is home to an extraordinarily rich biodiversity and was not fully explored by non-Indigenous people until well into the twentieth century.

This painting also tells an ancient story, or dreaming. In the religion of indigenous Australians, the Dreaming refers to stories about the creation of the world by ancestral beings. Dreamings explain how the universe was created, how the land was shaped, and who and what came to live in it. They provide guidance on how to behave and why, where to find certain foods, and much more. Above all, Dreamings teach people to live in harmony with each other, animals, and the land. Aboriginal people themselves more frequently refer to the Dreaming in English as "the Law," the unifying principle which brings together and governs all people, places, and things. The Dreaming is not a finite period of time, but is believed to be continually occurring and is ever-present in Aboriginal Australian culture.

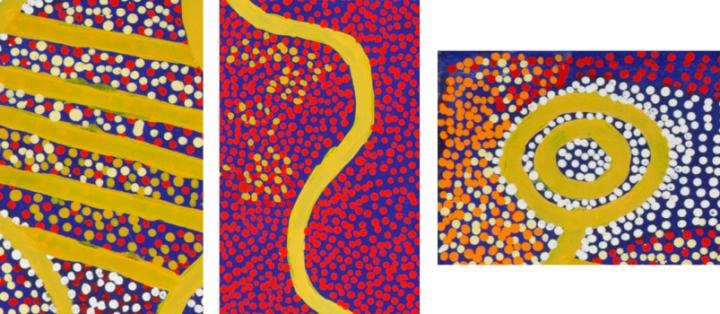

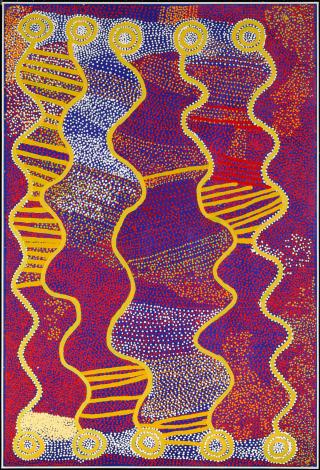

The painting recalls the important narrative of two Ancestral men who "sang" or summoned down the rain. They unleashed a great thunderstorm that ultimately created the large underwater wells that are represented by the repeated concentric circles. These "water holes' provide both physical and spiritual sustenance to the region's Warlpiri people. The long curving yellow lines in the painting, represent the fast-flowing rivers that form after heavy rain. The lines that cross between the travel lines suggest the lightning and rain-making clouds. The fields of colored dots allude to the flowering of the desert after the rain but the energy that they create on the surface of the canvas also suggests the continual spiritual presence of the ancestors. Overall, the painting captures the transformative effect of water as it courses through the dry desert.

For hundreds of years, Aboriginal peoples depicted Dreamings by painting them in the sand or on rocks or their bodies during ceremonies. Only recently—beginning roughly fifty years ago—did they begin painting Dreamings on canvas. Similarly, Shorty Jangala Robertson has only been painting for the art market since the mid-1980s, but he has been painting in ceremonial contexts for most of his adult life. As a senior Warlpiri man, his iconography is derived from sacred ceremonies, from designs that are incised or painted onto shields, wooden dishes, boomerangs and bodies, as well as those created for large three-dimensional ground mosaics. These sacred designs and the stories they reveal are reserved only for members of the community. Robertson modifies these designs for the public, and re-presents them on canvas as a way to demonstrate cultural knowledge, identity and pride. The incentive to paint comes from a desire to pay homage to the shape-shifting Ancestors who first gave Walpiri people these creation narratives and the designs with which to illustrate them.