Exhibitions Archive

Exploring the Excesses of Human Emotion

The Tortured SoulMyth, Cult, and Daily Life

Poseidon and the SeaThe world is comprised of objects. These discrete items acquire meaning through relationships and context, yet are defined by their own autonomy. To give order to the things that surround us, we create categories, which, in turn, rely upon cultural connotations that impart meaning, value, and significance. The common language of things can convey a multiplicity of ideas such as concerns, class, or interests. The audience interprets the subjects by and through the objects that surround them.

Works of art present a special category as they occupy several object worlds simultaneously. Artworks epitomize Graham Harman’s definition of a “real object” as one that has not an outer effect, but an inner one. The tactility of the object is, of course, present, but the value lies not purely in its physical qualities, but in what it evokes.

This exhibition was curated by Katie Hornstein, assistant professor of Art History, and Jane Carroll, senior lecturer of Art History, in conjunction with their class Introduction to Art History II. Students used these works of art for a writing assignment. This exhibition has been made possible by the Harrington Gallery Fund.

Representations of Biblical Women from Sixteenth-Century Germany

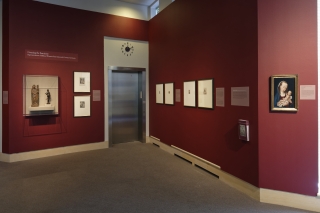

Creating the FeminineSelections from the Hood Museum of Art

The Beauty of BronzeBronze—a combination of copper, tin, and small amounts of other metals—has long been prized for its preciousness, endurance, and ability to register fine details and reflect light. It is strong and durable, making it ideal for modeling expressive gestures, yet—in molten form—it is malleable enough to be suitable for creating intricate shapes. The term “bronze” is often used for other metals as well, including brass, which is an alloy of copper and zinc.

There are two basic methods of casting a bronze in order to make multiple versions of the same design. Sand casting—developed in the early nineteenth century in Europe—is a relatively simple and less expensive technique that relies upon disparate molds made of compacted fine-grained sand that allow for easy production and assembly. Traditional lost-wax casting uses wax models in two manners, or methods, both of which date from antiquity. In the “direct” method, the original wax model itself is used (and thereby destroyed); in the “indirect” method, reusable plaster molds are taken from the original wax model.

The medium’s intrinsic tensile strength and ability to render precise features and various surfaces have been applied to a variety of objects, including vessels, implements, portraits, animals, and figurines. The examples on display here document the worldwide attraction to this remarkable material from antiquity to the early twentieth century.