ELIZABETH RICE MATTISON, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Academic Programming

Hood Quarterly, summer 2023

Many images of war celebrate victors' successes and soldiers' bravery, yet other representations record instances of trauma and victims' suffering. The exhibition Recording War presents depictions of conflict that enable viewers to reflect on the human experience of violence. Focused on European prints and drawings, dating between 1500 and 1900, the exhibition brings together familiar images from Francisco de Goya's Disasters of War series (1810–20) with less well-known works. Six themes emerge from the images: the actors of war, bodies in anguish, emotions of trauma, witnesses to violence, resistance to conflict, and the aftermath of loss. Drawn entirely from the Hood Museum's renowned collection of European works on paper, this exhibition reexamines how such images provide essential records of unwritten histories of loss and violence, resisting standard accounts of victory and triumph.

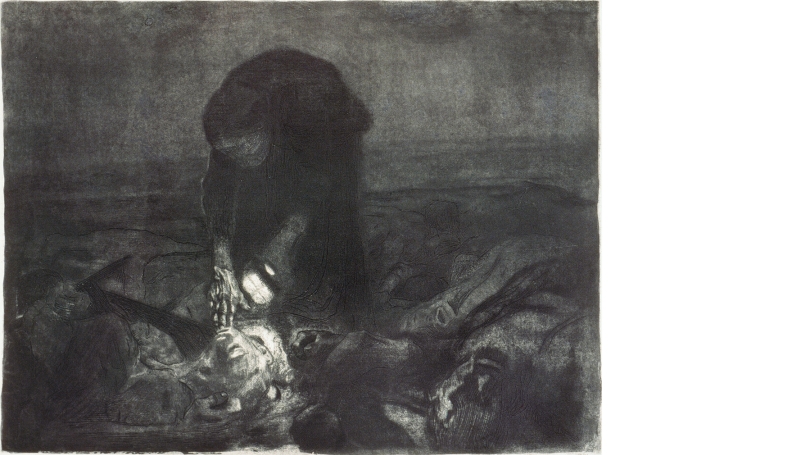

Recording War calls attention to the people represented in images of violence, humanizing the subjects and considering them as historical figures. While the names of battles, generals, and treaties are known in archival documents, the identities of women, children, people with disabilities, and civilians are more often lost. Nevertheless, the works in this exhibition offer a testament to the humanity and suffering of these people, recovering their unwritten narratives. For instance, Käthe Kollwitz's poignant image of a woman searching a battlefield exemplifies this role. Nearly obscured in the darkness, she bends to turn over the corpses of fallen soldiers. The face of one young man appears in the beam of her torchlight, disfigured and swollen with decomposition. Perhaps in search of a loved one, she transcends time, recording instead feeling in the aftermath of battle. The artistic record of the brutality of war served not only as evidence of events but also as a means of coming to grips with the various tragedies.

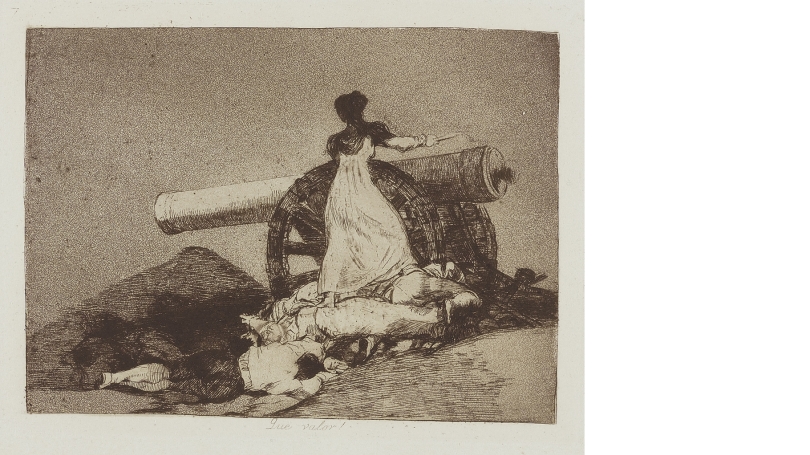

Often working in series, artists could create visual narratives that carried across multiple images to describe the nuances of war's effects. Embracing this type of production, Francisco de Goya's 80-print series excavates civilians' experiences during the Napoleonic French Empire's occupation of Spain between 1808 and 1814. The seventh print in the series is the only one known to document a specific event. In 1808, as the French attacked Zaragoza, a woman named Augustina joined the fight when too many of her nation's soldiers had been killed or injured. Here Goya highlights the woman against a dark background, her white dress standing out as a beacon of hope. Her face hidden, she becomes an abstracted symbol of national valor. In addition to Goya's prints, the exhibition features work by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), French printmaker Jacques Callot (1592–1635), Dutch publisher Gerard Valck (1610–1664), and French caricaturist Honoré Daumier (1808–1879). Together, these artists address a variety of martial conflicts, such as the German Empire's ongoing clashes with the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), and the Franco-Prussian War (1870). Their images shape societies' memories of these critical moments in time.

Such images can also complicate history. Dürer's Landscape with a Large Cannon was printed in 1518, as conflict between the German-speaking states and foreign powers grew (see the cover). Five caricatured Turkish men face a cannon, guarded by a German mercenary. While the predominantly Muslim Ottoman Empire was rapidly expanding, prompting German fear of conquest, this print does not feature battle. Instead, the German soldier and Ottomans only look at one another. For all that the states were enemies, they were linked by trade. This print suggests the complex relationship between Christian European and Muslim states, one marked by both war and exchange.

At its heart, the exhibition analyzes how images construct history. Prints and drawings are particularly primed for this capacity given their replicability, relative affordability of materials, and methods of production. The violent acts etched by Francisco de Goya or Jacques Callot rarely appear in paintings of the period. In his series of prints made as the Thirty Years War still raged, Callot include a grisly image of death. La pendaison (The Hanging) features soldiers accused of war crimes now stripped bare and hung from a tree. Although the soldiers have themselves committed atrocities, they are now subject to grotesque punishment. The dense cluster of dangling bodies offers a haunting condemnation of the continuing horrors of war. The rapidity of execution, as well as circulation, of such images further contributes to the documentary role of paper, allowing artists like Callot as well as Édouard Manet and Honoré Daumier to quickly respond to contemporary conflicts. Recording War presents works on paper as alternative historical evidence that preserves not merely the actions of war but also its physical and mental costs, centering the voices of now anonymous victims, witnesses, and actors in war.

Recording War: Images of Violence, 1500–1900 is organized by the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, and generously supported by the Leon C. 1927, Charles L. 1955, and Andrew J. 1984 Greenebaum Fund