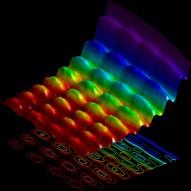

ABOVE Fig. 1. Light photographed as a wave and a particle. Photo by Fabrizio Carbone / EPFL

Introduction

In developing the concept for the Hood Museum of Art’s fall 2017 exhibition Resonant Spaces: Sound Art at Dartmouth, Amelia Kahl and I posited that sound is a material of art, one that can be compared with other materials such as wood, glass, paint, and metal. While sound can be deployed as an artistic material in the sense that it can be differentiated, changed, and transformed, in its audible form it exists only briefly, in a liminal space between the material and immaterial. Even the term sound art has been met with criticism, particularly around the idea that sound art is restrictive in that it limits the extent to which sound plays a role within art in the broadest historical and practice-based contexts.1 Yet scholar Christoph Cox argued successfully for the use of the term sound art as one that describes art that engages and even, at times, elevates the background noise of everyday life to become the art itself.2 Sound art in this context is therefore site-specific in the sense that acoustics, ambient noise, and other factors such as social and psychoacoustic contexts influence its transmission and reception.

Light—as an art medium, operates similarly between the material and immaterial, exhibiting properties of both a wave and a particle (fig. 1). When considered together, sound and light contain extraordinarily similar physiological and phenomenological properties: both light and sound can be harnessed from natural occurrences, such as sunlight or wind, or can be generated from artificial sources such as light-emitting diodes and loudspeakers. Both can behave as waves, and because of this they can be measured in terms of frequency through time. To this extent, even the most static sound and light works are time-based phenomena. Works created with light or sound are also subject to both perceptible and imperceptible phenomena in an environment. For instance, non-visible light or non-audible sound may have significant influence on the behavior of surrounding waves and their reflections, affecting multiple elements ranging from the reception of the work by visitors to the documentation process.

Given the overlap between light and sound, this essay examines commissioned sound art works created for Resonant Spaces in relation to topics of perception and environmental minimalism overlapping with light art. Specifically how the artists approach, control, and even restrict sound in their artistic practices to guide the visitor toward a particular experience; how the artists responded to their selected locations; and how sonic environmental conditions influenced or participated with the resulting art.

Seven of the eight artists featured in the exhibition—namely, Julianne Swartz, Alvin Lucier, Jacob Kirkegaard, Bill Fontana, Laura Maes, Jess Rowland, and Christine Sun Kim—were commissioned to produce site-specific works. As curators, Amelia and I were directly involved with the development, installation, and technological aspects of these new works. We had frequent conversations with the artists and conducted reviews of their works in progress, and the majority of the artists made site visits with us to select the Dartmouth campus location that best fit their vision.3 The resulting process illuminated the artistic practices of the individual artists, but also revealed aspects of sound art that speak to broader thematic areas in contemporary art—particularly the unique qualities and challenges facing light art, time-based art, and ephemeral art.